Liszt and Petrarch

Today, Liszt and Petrarch. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

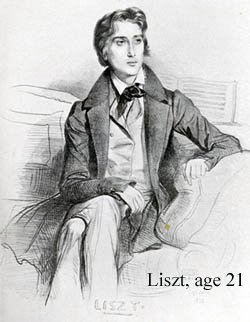

Franz Liszt was the rock star of the early 1840s -- a handsome genius with an animal instinct for the stage, a child prodigy who'd come full flower. He was born in cosmopolitan Hungary, but never really mastered that language. Among his early teachers was composer Antonio Salieri -- a better person than the movie Amadeus made him out to be. Salieri ultimately had a profound influence. Like the young Mozart, Liszt finally transcended his prodigy persona to become a great and a prolific composer.

When he was twenty he heard Paganini, and he determined to do for the fully evolved piano what Paganini had done for the modern violin. I suppose that included becoming a similar cult figure. But he also revealed the piano's full potential -- in his own compositions and in transcribing Paganini into a virtuoso piano literature.

When he was twenty he heard Paganini, and he determined to do for the fully evolved piano what Paganini had done for the modern violin. I suppose that included becoming a similar cult figure. But he also revealed the piano's full potential -- in his own compositions and in transcribing Paganini into a virtuoso piano literature.

But let's catch up with Liszt at the age of 26. The Lisztomania craze still lay ahead of him. For three years he'd been living and traveling with the Countess Marie d'Agoult, who'd left her husband, for him. Marie wrote under a male pen name -- Daniel Stern. Just as Liszt competed with his sometime friend Chopin, Marie competed with Chopin's companion, the woman writer George Sand.

Liszt called these his years of pilgrimage. And, I suppose, if we're to know this wild genius, that period helps explain him. As he shaped himself into a composer, he quoted Petrarch and Dante in letters to the Countess. Now he visited the Italy of these two great writers, both rock stars in the High Middle Ages. And he shaped musical ideas upon their poetry.

Petrarch had honed a new poetic form, the sonnet. His father had been Dante's friend, yet Petrarch avoided the subject of Dante. He was striking out in a new direction -- setting the stage for Renaissance humanism. Yet his philosophy was powerfully grounded in St. Augustine -- whose ideas shaped medieval theology.

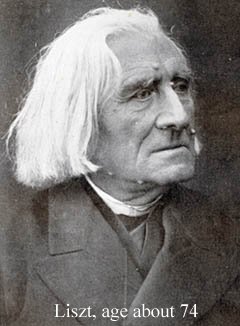

Perhaps that's why Petrarch so appealed to Liszt. Both rewrote our world view; both mirrored Augustine's struggle with Earth and Heaven. As Petrarch spun out his Romantic love of Laura, we realize it was not about Laura at all. It was about warfare between flesh and spirit. The inveterate womanizer and ardent Catholic Liszt took minor holy orders when he grew old. But, at 26, he merely set three of Petrarch's sonnets as songs.

Here's one text:

Warfare I cannot wage, yet know not peace;

I fear, I hope, I freeze again;

Mount to the skies, then bow to earth my face;

Grasp the whole world, yet nothing can obtain.

Petrarch's words are pure Augustine. They're also Liszt himself, on his long twisting path of self-formation: a simmering mixture of Mephistopheles and monk -- sensual, generous, moralistic -- all at once. From those contradictions came so much. But then, what should we expect when we encounter the creative daemon, and the creative angel, standing in a single pair of shoes.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

A vast amount of information about Liszt and Petrarch is to be found on the web and in Encyclopedia articles. See also the Liszt article in The New Grove Dictionary of Music & Musicians. Stanley Sadie, ed. (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2001).

I am particularly grateful to two UH colleagues, Rob Zaretsky and Richard Armstrong for their extensive and cogent council on this episode.

Of particular interest might be F. Liszt, Franz Liszt: Selected Letters. tr. and ed. by Adrian Williams, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.)

P. Stock-Morton, The Life of Marie d'Agoult alias Daniel Stern. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2000). Also, if one reads French, one may trace the Countesses side of the conversation with Liszt in Marie de Flavigny, comtesse D'AGOULT, Correspondance Générale. (Paris: Honoré Champion Éditeru, 2003).

For some light on Petrarch's reticence about Dante, see a letter in which he distances himself from Dante without using his name. Here Petrarch suggests that Dante was too interested in his own glory (rock star status). Richard Armstrong points out that the place and the use of personal glory was a strong concern of Petrarch's. See: Francesco Petrarca, Letters on Familiar Matters:XVII-XXIV. Tr. Aldo S. Bernardo (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1985): pp. 202-207.

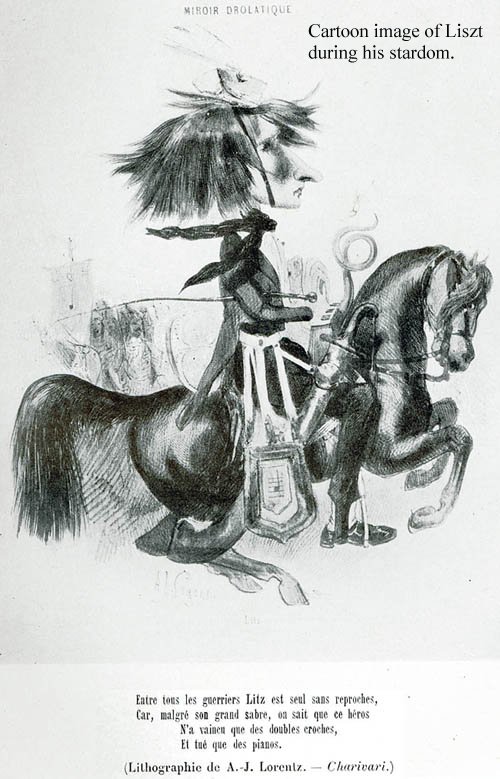

All images are from M.-D. Calvocoressi, Franz Liszt. (Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1905)

This episode was triggered by a performance of Liszt's piano version of his song based upon Petrarch's Sonnet 104: Sonetto 104 del Petrarca S.161, No.5, by UH pianist Timothy Hester on March 4, 2007. (In Italian listings, BTW, this sonnet appears as No. 134.)

The full text of Petrarch's Sonnet No. 104

WARFARE I cannot wage, yet know not peace;

I fear, I hope, I burn, I freeze again;

Mount to the skies, then bow to earth my face;

Grasp the whole world, yet nothing can obtain.

Pris'ner of one who deigns not to detain,

I am not made his own, nor giv'n release.

Love slays me not, nor yet will he unchain;

Nor life allot, nor stop my harm's increase.

Sightless I see my fair; though mute, I mourn;

I scorn existence, yet I court its stay;

Detest myself, and for another burn;

By grief I'm nurtured; and, though tearful, gay;

Death I despise, and life alike I hate:

Such, lady, do you make my wretched state!

This translation is a modification of G. F. Nott's more archaic version.