Steam Boilers

Today, steam boilers for the new steam engines. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Richard Hills interrupts his history of the steam engine, to give us a chapter titled Good Servants but Bad Masters. He's finished describing the early engines. Now he pauses to say something that cuts to the bone of inventive development: Steam engines were fine servants but, as their creators concentrated on the engine, they neglected the boiler. A steam engine needs a steam boiler -- and a simple teapot will not do.

Engine builders before James Watt had worked with both high and low pressure steam. For high pressure, Thomas Savery tried to build small boilers of soldered copper. The solder softened and he had a lot of trouble. Thomas Newcomen built low pressure engines, so his boilers could be much larger -- typically a five-foot diameter riveted lead dome resting on a cylinder of riveted wrought iron. They called his boilers haystacks because of their shape.

But both types of boilers were just big teapots -- pools of water heated from below. Watt's engines went only to modest pressures. He started out using haystack boilers, then switched over to something called a wagon boiler. It looked like a long covered wagon. But it was still just a big teapot.

All the while, people struggled with materials -- soldered coper, wrought iron, cast iron. Not until the mid-19th century would boilers be made of Bessemer steel. But engine builders somehow kept dodging the larger question: How to expose water to heat most efficiently?

When they needed more steam they just built bigger teapots. In Watt's time, one maker built a spherical boiler twenty feet in diameter. It's no surprise that something that large blew up. It flew 150 feet through the air and many people died.

Not 'til the early 1800s did engineers start seeing more than a simple teapot when they thought about boilers. Steam locomotives came into their own, then steamships. They needed small engines, and that meant high pressure. Engineers finally had to start thinking about how to manage a great deal of heat flow in boiler that was small, very strong -- and still safe.

A few 18th-century visionaries had talked about carrying flame through a bath of water in a pipe -- or carrying water through the flame in a pipe. But Watt kept using big teapots. He had to have twelve square feet of heating surface for every horsepower. It took the stimulus of the railroad to change that. Today, only a small fraction of a square foot produces one horsepower.

It's an old story: a big old out-of-sight tank had little curb appeal. All the fun drama lay with the engine. The abstract problem of manipulating heat flow in a boiler seemed distant from power production. You see the same thing today. We focus on the car, and forget its exhaust pipe, or the gas pump. It sometimes takes a long time for a tail to catch up with a dog.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

R. L. Hills, Power from Steam: A History of the Stationary Steam Engine. (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989).

For a discussion of heat flow as it occurs in boilers, see J. H. Lienhard IV and J. H. Lienhard V, A Heat Transfer Textbook, Ch. 3. This is available free of charge online: https://web.mit.edu/lienhard/www/ahtt.html

A few codicils to this episode: Newcomen started out using soldered copper, then he switched to wrought iron. Watt first used haystack boilers then switched to the wagon type. On the matter of square feet per horsepower, modern power plants require only around 0.02 square feet per horsepower. That looks like it's 600 times better than Watt's boilers. But Watt's engines were much less efficient. They typically required 20 or 25 times as much steam. That means modern heat exchanger design makes our boilers around 25 times as effective as Watt's.

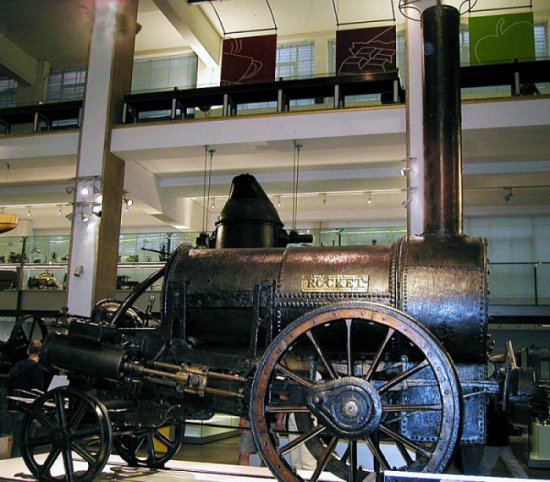

Below: A Newcomen haystack boiler, and Robert Stephenson's early locomotive, The Rocket. Only the dome of the Haystack is visible, the rest being encased in brick. Most of what we see of the locomotive is boiler. The actual engine is the cylinder in the lower left of the picture. (Both images from the London Museum of Science, photos by JHL).