Kitty Litter

Today, we buy a box of kitty litter. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

When we acquired our second cat, we decided to close off our cat door to the outside. That meant getting serious about maintaining litter boxes. We have, ever since, experimented with the dazzling variety of litter offered in stores. Along the way, we've learned so much about the role of compromise in engineering design.

Consider what a good cat litter should do: It should suppress odors, absorb, be biodegradable, nontoxic, and inexpensive. If you have more than one cat, both should be willing to use it. It shouldn't stick to paws, or between claws; yet it should clump enough to localize waste. And it's nice if it's flushable. But none of these features matters if your cat doesn't want to use it.

Now writer Curt Wohleber traces the design evolution of the stuff. Litter boxes existed before 1947. Owners had simply lined them with sand, sawdust, or torn-up newspapers. Then one of those moments -- like Newton's Apple or Goodyear's spilled chemicals:

Edward Lowe, back from the army was working in his father's supply store when a next door neighbor asked him if he had any sawdust for her litter box. Lowe did not. However, he was selling fuller's earth under the brand name Dri-Spot. Fuller's earth is a clay-like material with fine absorbent properties.

Fuller's earth was replacing the sawdust that'd been widely used to absorb spills. Sawdust had recently been banned from factory floors because, as it absorbed grease and oil it became a terrible fire hazard. You may've seen sawdust used on old-time barroom floors. In any case, Lowe now stocked fuller's earth in place of sawdust. So he suggested to his neighbor that she try it.

Fuller's earth fit the bill on many fronts. It absorbed liquid, clumped, also absorbed ammonia ions to reduce odors, and it didn't adhere to cat feet the way sand did. Lowe began putting the stuff in bags. He labeled them with as Kitty Litter (a name that would truly stick), and aggressively went to work to selling them. Just as 3-M Company created a market for Post-It notes by giving them away for several years, Lowe gave bags of his Kitty Litter to pet stores until he'd created a demand.

He couldn't patent fuller's earth, so he built a huge enterprise with no protection. But, Kitty Litter somehow sold below the radar of potential competitors. Clorox finally tried to compete with it by introducing a product called Litter Green, made from alfalfa. But the cats saved Lowe; they wouldn't use Litter Green. Not until the 1980s did companies seriously began inventing improved litters.

Now we walk the rows of boxes, trying to make the right compromise while our cats add their opinions. Kitty Litter is no longer a brand name, but a whole class of products. And Wohleber makes a telling point: Lowe began a great demographic shift in American pet-keeping from dogs to cats. Commercial cat litter has made cats welcome in our households as they had never quite been -- before it.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

C. Wohleber, Cat Litter. Invention & Technology, Summer 2006, pp. 8-9.

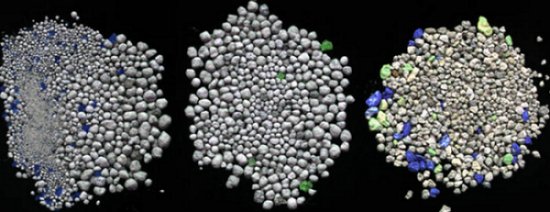

Some typical commercial litters, left to right: Ever Clean, Tidy Cats Small Spaces, Tidy Cats Crystals Blend