Cradle of Civilization

Today, we look for the cradle of civilization. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

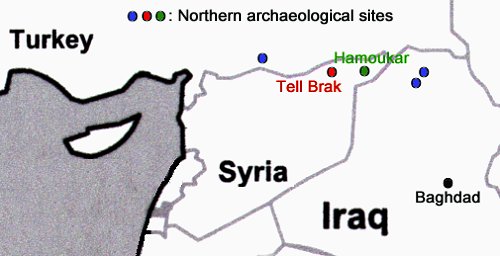

I'm struck by a photo of a lean tanned woman, 78 years old, in the new Science magazine. She's Joan Oates, in charge of excavations of Tell Brak, Syria. Tell Brak is one in a line of such archeological digs, strung out east and west, close to Turkey's border with Syria and Iraq. Oates has been digging in this region since the 1950s. Writer Andrew Lawler tells how she met her now-deceased husband David Oates here, as well as archaeologist Max Mallowan and his wife Agatha Christie.

It's long been a tenet of Archaeology that civilization arose in Mesopotamia -- the fertile triangle that embraced Baghdad and the region south of it. That region showed a high degree of urban organization almost 5500 years ago. But these sites on the lower edge of western Turkey's mountains are older still. And they lie a couple hundred miles north and west of Baghdad.

Tell Brak is the largest. First settled twelve thousand years ago, it's where Oates and others are finding layer upon layer of early construction. The dig has revealed complex urban development and monumental construction from over six thousand years ago. Surrounding the Tell, or central hill, is what one archaeologist calls an urban sprawl of 115 sites -- an area twenty miles in diameter.

Fifty miles east of Tell Brak is the Hamoukar site with ruins of a city almost six thousand years old. Much obsidian, and many large storage jars, suggest that it was a trading center.

Those northern cities appear to've peaked just about the time cities like Babylon and Uruk were taking form in the Fertile Crescent. And here the fun begins: Scattered in the ruins of Hamoukar, over a thousand small clay missiles have been found, along with over a hundred more the size of baseballs. There's also evidence of a great deal of damage having been done by fire.

That and other evidence suggests a Panzer attack from the south. A growing number of archaeologists are beginning to think that the upstart cities to the south overwhelmed the old world to the north. And that they attacked with slings and fire brands.

One idea is that improved technologies of shipping and trade gave the cities along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and edge in their development that they didn't have before. Cities on that flat land, with its many waterways, now spurred one another on, through the medium of commerce. The evidence now suggests that the once-great northern cities simply became conquered outposts.

Perhaps, but the time this program reaches reruns, the matter will be better resolved. Meanwhile, I look at that photo of Joan Oates at 78. She's looking at a civilization that flourished a mere 78 of her lifetimes ago -- do the arithmetic. Couched in those terms, it all seems so recent. Maybe that's why we still find it necessary, 78 lifetimes later, to bring about change with our own missiles and torches. Civilization is still very young.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

A. Lawler, North Versus South, Mesopotamian Style. Science, Vol. 312, 9 June, 2006. pp. 1458-1463.