The Tarrant Tabor

Today, a real estate developer builds an airplane. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

After WW-I, airplane makers set out to do what their dirigible-building cousins had done -- to create great flying hotels. They made some pretty wild machines. The body of the 1921 Caprioni seaplane was a huge houseboat for a hundred people -- a triple triplane with nine wings, eight engines, and so many struts that it looked like a wood-framed apartment building under construction. It got sixty feet in the air, then crashed into Lake Maggiore.

Later [1934], there was Tupolev's Maxim Gorky with a wingspan over 200 feet, eight engines, a movie theater and a radio station on board. It collided with a small escort plane on a propaganda flight. Everyone died.

Then there was Walter George Tarrant's flying monster. Tarrant, born in England in 1875, showed an early talent as a builder -- not of airplanes, but of houses. He set up business at the age of twenty. Working in the tradition of the Arts and Crafts Movement, he created an elegant thousand [exactly 964] acre housing development in 1911 -- complete with golf course. That sort of thing is common enough today, but it was quite daring a century ago.

WW-I found Tarrant putting women to work building prefab wooden huts for the military, and assembling them in France. This was before Nissen and Quonset huts were invented.

Then, late in the war, Tarrant used his construction talents to create a huge bomber, intended to reach Berlin. He was almost surely thinking beyond war to civilian transport. He finished his 22-ton behemoth, the Tarrant Tabor, six months after the Armistice.

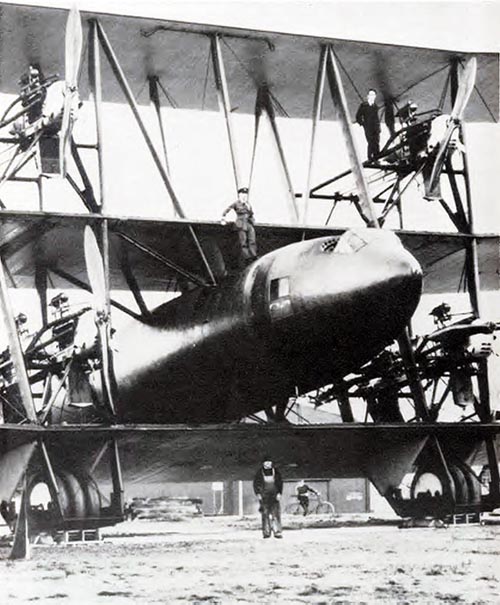

Photos of the Tabor are awesome -- a wingspan greater a Boeing 707, six engines between its three wings. A man standing on the fuselage, back against the middle wing, looks like a toy soldier.

The Tabor's first takeoff was going well enough while the pilots used the lower four engines. Then they put power to the two engines below the top wing. That was a mistake. Located so far above the Tabor's center of gravity, their turning moment nosed the plane over. Both pilots were killed.

Tarrant went back to his distinguished career erecting gracious buildings, but his brief flirtation with flight had been only a harbinger. Others succumbed to big-airplane fever. Airplanes just a bit too large to manage kept appearing: the B-19, the B-36, and ultimately the fabled Spruce Goose. Even the airworthy ones were regularly trumped by smaller and better all-around designs.

Size is a seductress. When we first learned to make steel-framed buildings we ran them up as high as the Empire State Building before we paused to question ourselves. Same with airplanes: On the whole, airplanes, like buildings, have kept growing, but slowly, as we widen the supporting technological base. All the while, we keep seeing the mad excess, the attempt to break away from the modulated rhythm of design evolution. That's what Tarrant tried to do. And it's what so many after him have tried to do, as well.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

P. Scott, The Wrong Stuff? (New York: Barnes and Noble, 2006): pp. 90-95. For more and Tarrant and his airplane, see the Wikipedia article.

The Tarrant Tabor, (image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.)