B-36

Today, we fall into a technological crack. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I suppose Howard Hughes' Spruce Goose is the yardstick we use to measure any really large airplane. But others have since beaten it. The Boeing 747, for example: It has a larger body and far greater carrying capacity.

One airplane that flew before the Goose came close to beating its numbers; but, unlike the Goose, it saw years of service. The B-36 bomber was conceived in 1941, before we entered WW-II. The government wanted an airplane that could make a ten-thousand-mile roundtrip, carrying five tons of bombs to a target. And it was supposed to fly almost four hundred miles an hour.

Douglas Aircraft was already working on a clunky behemoth called the B-19. Then Consolidated Aircraft undertook the B-36. By then, we had Flying Fortresses and Liberators. They were the heavy bombers that would be used throughout the war. But both looked small alongside this dream of aerial immensity.

War never has been friendly to radical new designs. The B-36 kept being shuffled off to the margins. Generals wanted its features, but more urgent demands crowded it out. The first B-36, not yet finished, rolled out of a hanger six days after the war ended. It didn't fly until another year had passed.

From then on, the B-36 served as a kind of airplane design laboratory. The first ones tried to carry most of their 200-ton weight on one wheel under each wing. Those wheels chewed up air-strips and had to be replaced with two four-wheel carriages.

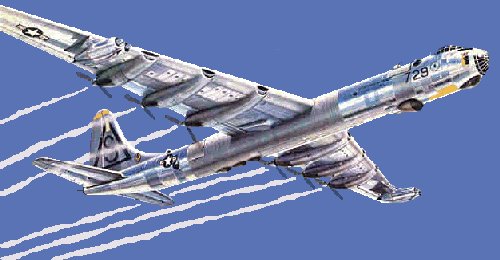

Its 230-foot wing carried six backward-facing propellers. But the future would be the jet engine. The B-36 compromised by adding a double jet-engine pod near each wingtip. With ten engines, the B-36 now did almost 440 miles-an-hour. And that's how it served the Strategic Air Command in the worst of the cold war.

All the while, designers used every trick to extend its usefulness. The wildest idea was adding attachments so it could carry its own short-range fighter planes along with it.

Consolidated also made a fat-bodied cargo version. It could carry a whopping fifty-ton load, but there wasn't enough demand for it. Then they made a huge passenger version, and -- sure enough -- it couldn't compete with the new jet airliners.

By 1959, the B-36 was made completely obsolete by the B-52 jet bomber. By then, almost four hundred had been built. And, in less than a decade of service, none ever dropped a bomb or fired a shot upon our largely imaginary enemy. By the way, Consolidated-Vultee called it The Peacemaker. Maybe it really was.

But it served the thankless role of straddling the epochs of the propeller and of the jet. It lost its struggle for survival only after countless inventive people had tried every way to keep it functional. Today, only four remain. And, like the Spruce Goose, they are all are museum pieces. None will ever fly again.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

M. K. Jacobsen & R. Wagner, B-36 in Action. (Illustrated by Don Greer) (Carrollton, TX: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1980).

This is the website of the Peacemaker Museum in Ft. Worth, TX: http://www.b-36peacemakermuseum.org/

Three images of the B-36 from various government sources. The lower one shows wingtip devices for attaching fighter planes.