Archerfish and Education

Today, an archerfish learns to shoot. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

A story is told about a great college swimming coach. His swimmers won NCAA Championships year after year. He was flamboyant, exciting, charismatic. He'd pace the rim of the swimming pool shouting instructions, adjusting strokes and body orientations. He had a fine eye for what each swimmer needed to do. Then one day, he tripped as he ran along the edge of the pool. He fell into the pool and drowned. It turns out he'd never learned to swim.

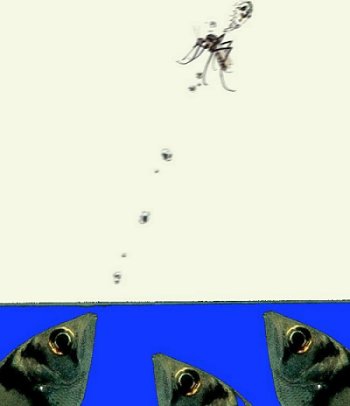

We laugh, not because it's ridiculous, but because we wonder if it really could happen. Can one function on the basis of a purely intellectual understanding of a physical skill? Well, meet the archerfish. This inch-long creature feeds on insects that it shoots out of the air. It spits water droplets from just below the surface, and nails flying insects five feet away. Think of all that involves. The fish has to lead the moving insect and adjust the angle of its shot as the prey moves away. It has to correct for the light refraction between water and air.

Now German ichthyologists study these fish. They find that, like top-notch swimmers, the fish have to practice. At first their technique is poor; their aim is lousy. They become fine marksmen only by trial and error practice -- as expected.

Then a startling discovery: When they put several inexperienced fish in the tank and fly insects over it, only one alpha fish practices. He becomes quite good at shooting down insects, while the others just watch. So the frustrated scientists finally remove that one fish. When they do, the other fish begin shooting down insects. They've become just as able as the one fish who'd practiced. They've learned entirely by watching, not at all by doing.

That flies in the teeth of all we believe about human education. It simply shouldn't happen that way. But it does. And, if that unfortunate swimming coach had been an archer fish, he wouldn't have drowned the first time he found himself in the water.

The catch is that we have to undertake so much without practice, in our complex world. That's what college should be all about -- preparing for the unexpected. We're so often told that people learn faster in the school of hard knocks. Well, they do -- up to a point. But we'd be dead in the water if we couldn't deal with things beyond our experience. That's what we do when we design any large system. Politicians and businessmen constantly deal with such issues, and they make a mess of them only some of the time.

You and I are more like archer fish than we realize. Indeed, that story about the swimming coach is flawed just because he would've been rather well prepared for his unexpected immersion.

All the most serious issues that rise in our face today are ones in which none of us can claim a whit of experience. Bismarck understood that, when he said, Only a fool learns from his own mistakes. The wise man learns from the mistakes of others

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

C. Brodie, Watch and Learn. American Scientist, Vol. 94,May-June 2006, pg. 218.

Wikipedia article about the Archerfish

Watch and Learn