George Henry Lewes

Today, a man of letters. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I've always stuttered-stepped over the Victorian term: man of letters. It's a term you would not apply to such great 19th-century writers as Austin, Wordsworth, or Dickens, however broadly they wrote. Man of letters referred more to public intellectuals who commented on literature and society -- Carlyle, Sand, Ruskin.

I'm just a hair suspicious of that breed. They often emerge as more elegant than the original, while they are, in fact, observers -- not originators. I mention this because I've just found a strange 1860 book: The Physiology of Common Life. It was written by the Victorian man of letters, George Henry Lewes.

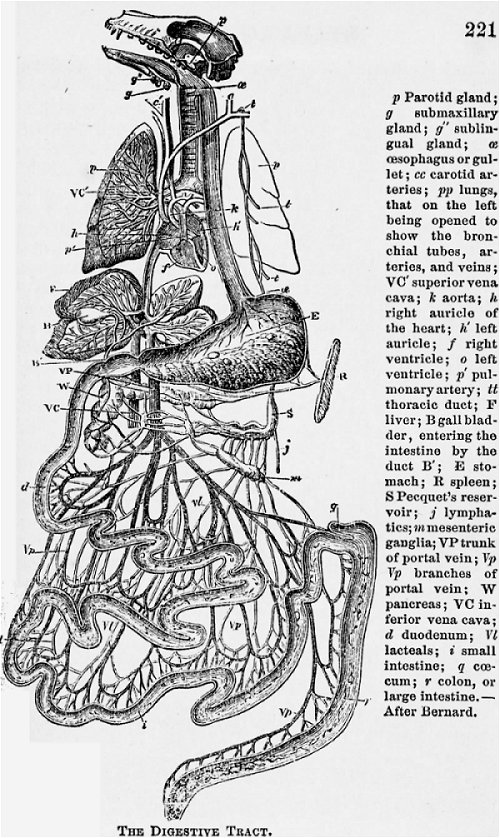

Lewes deals with sensory perception, consciousness, nourishment, digestion, blood circulation, body heat, respiration. He addresses all the right questions, but he comes up short on hard science. He's heavy on anecdote, and he devotes long passages to trashing the work of the great German chemist, Justis von Liebig.

Lewes deals with sensory perception, consciousness, nourishment, digestion, blood circulation, body heat, respiration. He addresses all the right questions, but he comes up short on hard science. He's heavy on anecdote, and he devotes long passages to trashing the work of the great German chemist, Justis von Liebig.

He's down on chemistry generally -- speaks of its radical incompetence to settle true physiological questions. Chemistry is in its cradle, and he seems unable to find value in that newborn babe.

Lewes tries to trace genetic influences of fathers and mothers on offspring. He devotes pages to specific children and their parents. He can't be blamed for not knowing about Y-chromosomes; but his failure to see the potential of science is quite spectacular. And his fine readable words flow on for six hundred pages.

Lewes was born the illegitimate son of a little-known poet in 1817. His father abandoned him when he was two, but his education, while spotty, covered a lot of ground. He learned French, and studied some medicine. He went off to London to become a journalist and hung out with the literati.

He married another free spirit, Agnes Jervis. They had five children. Meanwhile Lewes developed a close friendship with a journalist named Hunt. When Agnes had four more children by Hunt, Lewes accepted their paternity. Lewes was meanwhile taking up a long affair with writer Marian Evans who wrote as George Eliot. It was, to say the least, a very odd skein of relationships.

He married another free spirit, Agnes Jervis. They had five children. Meanwhile Lewes developed a close friendship with a journalist named Hunt. When Agnes had four more children by Hunt, Lewes accepted their paternity. Lewes was meanwhile taking up a long affair with writer Marian Evans who wrote as George Eliot. It was, to say the least, a very odd skein of relationships.

Lewes wrote and wrote. He worked with Mary Shelley on a biography of her husband, which he never finished. He seriously damaged his friendship with Dickens when he criticized his bad science in Bleak House. (A Dickens' character spontaneously combusts after drinking too much liquor.) I wonder if Lewes knew that his whipping boy, von Liebig, once testified that an alcoholic woman, thought to have died by spontaneous combustion, had actually been murdered.

But, as complexity and contradiction increase, my position softens. It's not enough that great writers and scientists exist; their work must be mixed, stirred, and brought to a larger public. Not everything these commentators say is right, but the public is smarter than we think. It eventually sorts things out correctly.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

G. H. Lewes, The Physiology of Common Life. (Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1860.)

See also, the entry on Lewes, George Henry (1817-1878) in the Dictionary of National Biography.

I am grateful to James Pipkin, UH English Dept., for his counsel.

Borrowed image of the digestive tract of a dog used by Lewes in his Physiology book.