Bush Pilots

Today, bush pilots. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Bush flying is pretty unfamiliar to most of us. It's done out of our line of sight. Yet, it has played a huge role in opening up regions which, by the end of WW-I, were inaccessible to rail, coach -- even horses. Most of places like Canada, Alaska, Australia, and New Guinea were thinly-populated by natives and only rarely visited by others.

But airplanes finally offered some possibility of getting into those areas. And a few flyers, whose appetite for danger had not been satisfied by War, turned toward the wilderness.

One of the earliest services was formed by a man who'd worked with the Canadian forest service. He hired a former British Navy pilot and borrowed two of the Curtiss HS-2L seaplanes that America had built to hunt German submarines off the East Coast.

One of the earliest services was formed by a man who'd worked with the Canadian forest service. He hired a former British Navy pilot and borrowed two of the Curtiss HS-2L seaplanes that America had built to hunt German submarines off the East Coast.

The HS-2L's body was a big kayak with two open cockpits. Its two wings had a 74-foot span, and sat like a truss bridge atop the body. It carried a ton of goods and/or people, cruised at 65 mph, and had a range just over 400 miles.

The service began by scouting fires and doing aerial photography in Quebec. Soon a fleet of HS-2Ls was delivering goods and people throughout Eastern Canada. Then Ontario set up its own provincial service and the whole operation might've taken on the appearance of legitimacy. But a gold rush occurred at Red Lake, Ontario, in 1926. It sparked a spate of new fly-by-night operations.

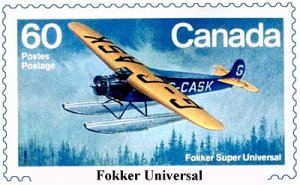

The HS-2L was still a work-horse, but now newer airplanes appeared. The Fokker Universal was a high-wing monoplane. Two pilots in an open cockpit and six passengers inside its cabin -- 118 mph, and a 700 mile range. It could be fit with skis, wheels, or pontoons. (Note, the cockpit has been enclosed on the Fokker Universal shown on the Canadian postage stamp.)

The HS-2L was still a work-horse, but now newer airplanes appeared. The Fokker Universal was a high-wing monoplane. Two pilots in an open cockpit and six passengers inside its cabin -- 118 mph, and a 700 mile range. It could be fit with skis, wheels, or pontoons. (Note, the cockpit has been enclosed on the Fokker Universal shown on the Canadian postage stamp.)

So bush operations spread north and west -- into the Yukon and Alaska. Conditions were ghastly -- crashes and death -- but the skill of the pilots became legendary. One, a man named Bob Reeve wrote on the side of his maintenance shack, Always use Reeve Airways. Slow Unreliable Unfair and Crooked. Scared & Unlicensed. Reeve Airways "The Best".

Reeve had flown mail over the Andes. He made and lost a pile of money. Then he stowed away in a steamer for Anchorage in 1932. He stowed away again on a boat to Valdez. There he borrowed an airplane and dazzled the owners with both his mechanical and flying ability. He was soon flying prospectors into the mountains and using glaciers as airstrips.

Meanwhile another bush pilot, Noel Wien, had built up a 175-airplane service. When Reeve went broke this time, Wien hired him. Now airplanes landed on real airstrips; and, in 1973, Wien bought five Boeing 737 jets. And so it was, when I spoke in Alaska, that a pilot flew me around the Kenai Peninsula in a light Stinson airplane. We used a concrete runway, and I could not summon even a shadow of a doubt that I was safe. It was fun, but an era was clearly gone.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

The Bush Pilots. (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1983)

For more on the Curtiss HS-2L click here.

For the Fokker Universal, click here.