Orukter Amphibolos

Today, trouble in the history books. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

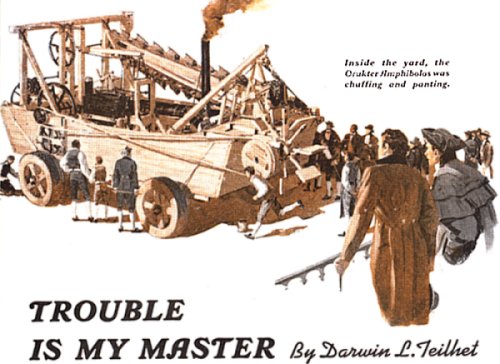

I t's a week after Pearl Harbor. I'm eleven, and the Saturday Evening Postarrives with the first installment of Darwin Teilhet's book Trouble is My Master. My father reads it to me -- all about a boy my age named Tack, who lived in 1804 and was always in trouble.

When Tack boasts that he's making a flying machine, he's in trouble for lying. But he's saved by a friendship with a crotchety inventor named Oliver Evans. Evans helps him design and build a huge kite, which he uses to carry a schoolmate aloft.

As backdrop to all this, Evans was building his steam-powered amphibious dredge, Orukter Amphibolos. I was in love with flying, so I focused on Tack's kite instead of the Orukter. But, unlike Tack and his kite, Evans was a real person in a fictional book. His Orukter dredge was also real, and here the fun begins.

Historian Steven Lubar looks more closely at the dredge -- a stunning accomplishment -- and he wonders if it too belongs in the fiction column. But who wants to put it there? That steam powered tour de force was decades ahead of its time -- traveling on land, navigating water, then doing the hard work of dredging! It may've been too good to be true; but it was also too good not to be true.

Lubar finds an upward spiral of claims by Evans. Those claims are bolstered by his supporters; but they're hardly mentioned by neutral observers. The very limited writings suggest that such a machine did run -- a year later than Evans claimed -- and that it stalled near his shop. Whether or not it'd been hauled to the water, and run as a steamboat, is not clear.

The reason Evans was plausible is that he was a great inventor. He'd invented a system of American millworks. His high pressure Columbian engine had a profound effect on the evolution of steam powered transportation in America. Yet trouble followed him, just as surely as trouble followed the fictional boy Tack.

Evans was crotchety; and, as he grew older, he exaggerated more and more. During the two centuries after he built his steam dredge, his later versions of its story became part of our history. Pick up almost any book on American technology, and there it is. The story works its mischief -- and its magic -- at the same time.

While I remember little of the novel, 65 years later, I do remember wondering if it was history or just a story. Of course, I was more interested in Tack's kite than in Evans' dredge. Yet the drama served its purpose. We'd just been drawn into a war that we could well lose, and my father was reading to me about early America's strength in the face of trouble.

Perhaps the Orukter dredge never was functional. But we live on stories. They buoy us and help us sort things through. Since Evans' Orukter makes a fine legend of our origins, I'll do what I can to make use of it. I just hope I can remember to use it without being so naïve as to entirely believe it.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

S. Lubar, Was This America's First Steamboat, Locomotive, and Car? Invention and Technology, Vol. 21, No. 4, Spring 2006. pp. 16-24.

D. L. Teilhet, Trouble is my Master, The Saturday Evening Post. Dec. 13, 20, 27, 1941, and Jan. 2, 1942. (Many scattered pages in each issue.)

Years ago, among my first programs in this series, was one that included the standard story of Evan's Orukter Amphibolos, Episode 264.

Below, an illustration by Donald Teague from the last installment of Trouble is my Master in the magazine.