Rudolph Ackermann

Today, architectural historian Margaret Culbertson tells us about a great chronicler of technology and art. The University of Houston, presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We find a time capsule from early 19th century England in an illustrated magazine produced by a German-born carriage designer. Like architecture or automobile design today, carriage design required proficiency in art as well as technology. It also could lead to great rewards, when royalty or the nobility commissioned custom carriages. Rudolph Ackermann excelled in the field after he moved to England, around 1784. But his career path veered dramatically seven years later, when he prepared a book of his carriage designs. He became fascinated with the making of books. Within three years he'd transformed himself into a publisher.

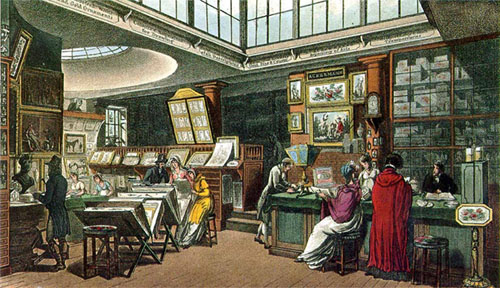

With his background in design, Ackermann naturally gravitated to illustrated books. He produced technical and artistic works and commissioned many artists to create illustrations. One was Maria Cosway, Thomas Jefferson's friend who was featured in the movie, Jefferson in Paris. Ackermann's attention to detail, eye for talent, and ability to coordinate authors, artists, engravers, printers, binders, and booksellers led to a huge body of work of extraordinary quality. After only seven years he'd published 63 books. When he died in 1834, the number was over 300.

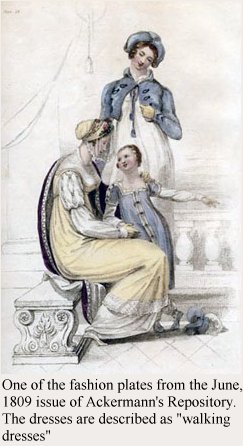

Ackermann started publishing a monthly magazine in 1809. It would continue for 20 years and circulate internationally. The title described its contents: The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, M anufactures, Fashion and Politics. It eventually evolved into a ladies magazine, but it continued to represent Ackermann's wide-ranging interests -- articles on water pumps, gas-lighting, and lithographic presses, along with fashion plates and furniture designs.

anufactures, Fashion and Politics. It eventually evolved into a ladies magazine, but it continued to represent Ackermann's wide-ranging interests -- articles on water pumps, gas-lighting, and lithographic presses, along with fashion plates and furniture designs.

The illustrations were the highlight. In this age before photography, they were all hand-colored prints, at least four per issue, for an astounding total of over 1,400. They depict early 19th-century England with amazing detail and vibrancy -- at least the England of the upper middle class -- clothing, furniture, room designs, houses, and country estates. Even tiny samples of recommended fabrics and wallpaper are attached to the pages.

Historians of art, architecture, decorative arts, and costume have mined Ackermann's magazine repeatedly over the years. Film and theater designers borrow costumes and interiors from its pages. Productions of the works of Jane Austen, in particular, often derive from The Repository, since Austen published her novels during the same years Ackermann produced his magazine. Consequently, our vision of Austen's characters and their world has been shaped by Ackermann's illustrations.

Ackermann's stated goals for the magazine were "to convey useful information in a pleasing and popular form." As often happens, our actions have repercussions beyond our intentions. Rudolph Ackermann did indeed "convey useful information." But, in the process, he created a treasure trove that still rewards exploration, and gives us the world of the nineteenth century.

I'm Margaret Culbertson from the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, where we too are interested in the way inventive minds work.

Margaret Culbertson is Director of the Hirsch Library, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and author of Texas Houses Built by the Book.

P. Agius, Ackermann's Regency Furniture & Interiors. (Ramsbury, Wiltshire: Crowood Press, 1984).

J. Ford, Ackermann 1783-1983: The Business of Art. (London: Ackermann, 1983.)

S. Jervis, "Rudolph Ackerman," in London, World City, 1800-1840. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992).

In Houston, one may make arrangements to view the Bayou Bend Collection copies of Ackermann's Repository through the Hirsch Library, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. (713-639-7326)

My thanks to Michael Brown, Curator, Bayou Bend Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, for suggesting that I explore the Bayou Bend copies of Ackermann's Repository. (MC)

A view of Rudolph Ackermann's London art gallery, called The Repository of Arts. Ackerman expanded on the gallery name for the title of his magazine. This plate was included in the first issue of Ackermann's magazine, published in January, 1809.