Triangles and Ecology

Today, triangles and ecology. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Three things happened yesterday, and they all converged: First, I took my Science magazine off to read at lunch. One article told about a team of cognitive scientists who visited the remote Mundurukú natives, living along the Amazon -- hunter-gatherers with no written language. They didn't even have words for numbers.

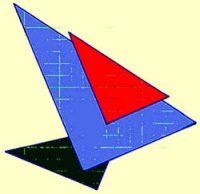

The scientists tested them with many sets of six groups of geometrical figures. Which group had a feature, unlike the other five? Five of the six might be pairs of right triangles in different sizes and orientations. The sixth might be a right triangle with an isosceles triangle. The tests weren't easy.

They found that 6-year-old Mundurukú children and 6-year-olds in the US did equally well. Children in both worlds have the same innate sense of geometrical logic.

When those tests were given to Mundurukú and US adults, the Mundurukú adults did about as well as their children. US adults did much better. Without a symbolic language to build upon, the Mundurukús' natural geometric ability could go no further.

That was on my mind at an evening reception and lecture sponsored by British Petroleum and the British Embassy. Cambridge professor Chris Rapley, Director of the British Antarctic Survey, spoke on global climate change.

At the reception, I met 12-year-old Paige, who told me about her 7th-grade math studies. She'd been mathematically dilating and contracting triangles positioned on graph paper. Naturally, her animation and interest reminded me of those Mundurukú children. She was building upon the same native ability she'd once shared with them. Then our conversation ended as she, and I, and the rest of the group moved into the I-MAX theater for the lecture.

At the reception, I met 12-year-old Paige, who told me about her 7th-grade math studies. She'd been mathematically dilating and contracting triangles positioned on graph paper. Naturally, her animation and interest reminded me of those Mundurukú children. She was building upon the same native ability she'd once shared with them. Then our conversation ended as she, and I, and the rest of the group moved into the I-MAX theater for the lecture.

Rapley told how Antarctic ice-core samples reveal Earth's gain in atmospheric carbon dioxide. Those data show CO2 oscillating between 140 and 280 parts per million over a 900,000 year period. Then, in the last century, it's risen to 380 parts per million.

He discussed the recent one-degree-centigrade rise in Earth's average temperature. He documented polar melting, and some of the more dire results that've already begun to follow our rising temperature.

He discussed the recent one-degree-centigrade rise in Earth's average temperature. He documented polar melting, and some of the more dire results that've already begun to follow our rising temperature.

This event, co-sponsored by a major oil company, underscored the fact that global warming is no fringe group concoction. We can no longer write its impact off as some Chicken Little scare. Warming is an acknowledged reality that hovers over us all.

So I thought once more about Paige and her triangles. The problem of global climate is terribly complex. Something must be done, but we struggle to see where even to begin effective assaults upon it. It certainly won't be solved with slogans. That's why our hope rides on 12-year-olds whose native ability can be drawn into those complexities. They still have the needed intellectual birthright -- the one that we all share, and which too many of us simply allow to lapse.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

See: C. Holden, Hunter-Gatherers Grasp Geometry. And S. Dehaene, V. Izard, P. Pica, and E. Spelke, Core Knoledge of Geometry in an Amazonian Indigene Group. Science, Vol. 311, No. 5759, pg. 317 and pp. 381-384.

Prof. Chris Rapley's lecture, North South East West: A 360-Degree View of Climate Change, was sponsored by Her Britannic Majesty's Consul-General at Houston, Judith Slater, and the Houston Museum of Natural Science, with a reception sponsored by BP, 6:30 PM, Monday, January 30, 2006.

My special thanks to Paige Christopher for her interest in math.

The Antarctic photos above and those below are taken from W. Filchner, Zum Sechsten Erdteil. (Berlin: Im Verlag Ullstein, 1922.) Click on the images below to see fine large scale photos of Antarctic ice.