Shaping Death

by Rob Zaretsky

Today, historian Rob Zaretsky sees Death turned into an enemy. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

"How can we live well?" It's our perennial question, but even more so America's, where the answers range from longevity and wealth, to happiness and health. But the public debate over physician-assisted suicide reminds us that dying well is as persistent a question.

The question is hardly new. And it was, for our ancient ancestors, no less perennial, yet far less controversial. Historian Philippe Ariès reminds us that death was a part of life. Medieval and early modern romances, chronicles and memoirs speak with one voice: when death knocked, the door was opened and the visitor was welcomed in remarkably similar ways.

Organization was essential. The dying person was responsible for the proper execution of his final exit. The doctor's principal task was not to delay death, but to guarantee that it was welcomed properly. And, indeed, the doctor wasn't alone. Family and friends gathered for the ceremony and the doctor was simply a face in the crowd. One and all understood their roles and the lesson that was imparted: they, too, would eventually be called.

The intimate relationship between life and death unfolded in unexpected places. The medieval and early modern cemetery was no less public place than the deathbed. For centuries, the activities we associate with the marketplace commonly took place in cemeteries, amongst the tombs and charnel houses. Merchants and scribes, musicians and dancers, jugglers and actors and, gamblers and the like sought to make a living in the company of the dead. When Hamlet clowns about with Yorick's skull, he's exceptional only in the fluency of his language.

By the late eighteenth century, language and attitudes began to change. Public authorities tried to stop profane activities in the newly redefined sacred spaces like the cemetery. At the same time, doctors began to sound the way they do today: the crowd of family and friends around the deathbed, they complained, complicated the job of attending to their patients.

Death thus got away from the dying person; it became the responsibility of others. It is only recently, with the rise of the hospice movement, that we're reminded of the ways in which we formerly responded to death. The recognition of death's finality, the planning for its arrival, the gathering of family and the redefinition of the physician's task: rather than confronting a brave new world, we seem to be returning to a simpler and older world. Ariès called this older understanding "tamed death." According to him,

the old attitude in which death was both familiar and near, evoking no great fear or awe, [is in] marked a contrast to ours, where death is so frightful that we dare not utter its name. I do not mean that death had once been wild and [is no longer], I mean, on the contrary, that today it has become wild.

And death has, in part, grown wild through the very tools with which medical science tries to domesticate it: an irony that would not be lost on Hamlet's creator.

I'm Rob Zaretsky, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

P. Ariès, The Hour of Our Death. (New York: Knopf 1981).

P. Ariès, Western Attitudes Toward Death. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 1974).

Robert Zaretsky is professor of French history in the University of Houston Honors College, and the Department of Modern and Classical Languages. (He is the author of Nîmes at War: Religion, Politics and Public Opinion in the Department of the Gard, 1938-1944. (Penn State 1995), Cock and Bull Stories: Folco de Baroncelli and the Invention of the Camargue. (Nebraska 2004), co-editor of France at War: Vichy and the Historians. (Berg 2001), translator of Tzevtan Todorov's Voices From the Gulag. (Penn State 2000) and Frail Happiness: An Essay on Rousseau. (Penn State 2001).

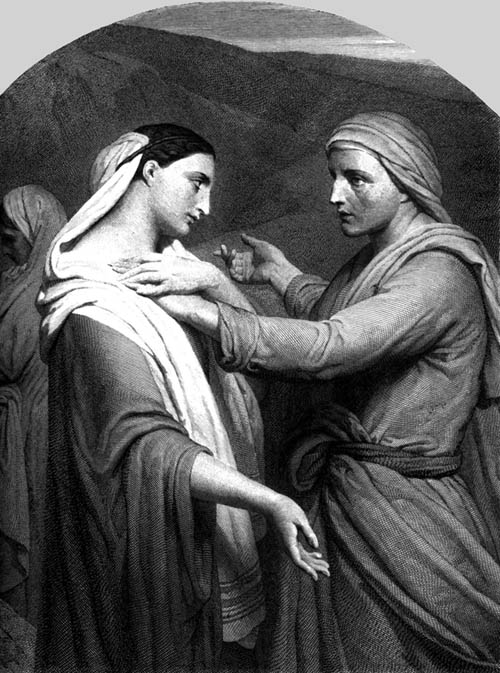

(clipart)