Figuring Out Science

Today, figuring out science in 1876. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Think about our science frontiers: What does String Theory tell us, what's dark matter, will a wormhole really take us to distant galaxies? Now tell me: Wouldn't it be something to be able to look back on all these conversations from the 22nd century?

I've been doing something like that with the 1876 Manufacturer and Builder magazine. Science was suddenly leaping ahead. A new production of cheap books on technology and science had been educating a surprisingly well-read American public.

The last remnant of alchemy, the caloric theory had just recently collapsed. Now electricity held center stage. Electric motors were embryonic. You could buy an arc light, but not yet a light bulb. The magazine exhibits a childlike awe, not only at all the new machinery, but also at all the science behind it.

So the magazine writers struggle with the details. One of them tries to determine which units are fundamental and which are derived -- time, length, mass, velocity, energy ...

Today, we flatly assert that mass, length and time are basic units. Today, the various bureaus of standards maintain measures of those three, and they derive the rest from them. The writer comes to the same conclusion, but he's just speculating. That was is not yet accepted physics. He also says something very odd about force: Since it's completely apart from matter, he deems it to be metaphysical.

Another hot topic was Earth's age. Fourteen years earlier, British Lord Kelvin had calculated a hundred million years -- far too long for fundamentalists and far too short for geologists. Now my magazine expresses surprise that France, with its Catholic orthodoxy, has announced a much older Earth. A French scientist has constructed a dubious argument, but it yields six billion years. Remarkably, he's only off by only around thirty percent.

The magazine thunders on: Amidst articles about new steam boiler designs, new musical instruments, and new cameras, science keeps appearing. The world is opening up like an oyster and curiosity is huge. What is the true nature of things?

You find flashes of wrong-minded rigidity, of course: One article argues that the human races are different species, with some superior to others. But, next to it, an article supports the new idea of evolution, and calls for more data to clarify it.

Well, we have those data today. Yet half of us want to pretend they don't exist. As I read this old magazine, I realize that our great-grandparents were often more scientifically savvy than we are. The magazine bubbles with discourse -- point-counterpoint, positions taken, positions yielded -- but all as the facts require.

I finally realize that this is about attitude. The young people who read this stuff learned to pose questions and then seek out answers. Then, armed with genuine curiosity, those people gave America its golden age of technological and scientific greatness.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. Eight, 1876. My thanks to Margaret Culbertson, Museum of Fine Arts Library, for lending me her copy of this fascinating source.

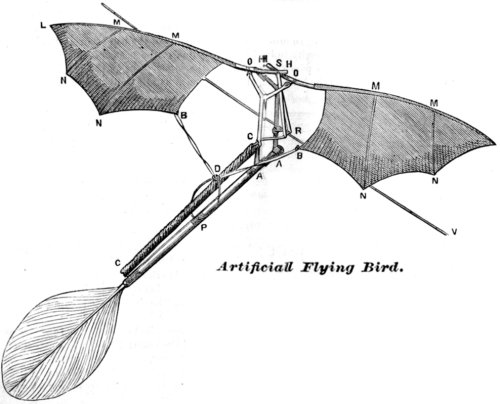

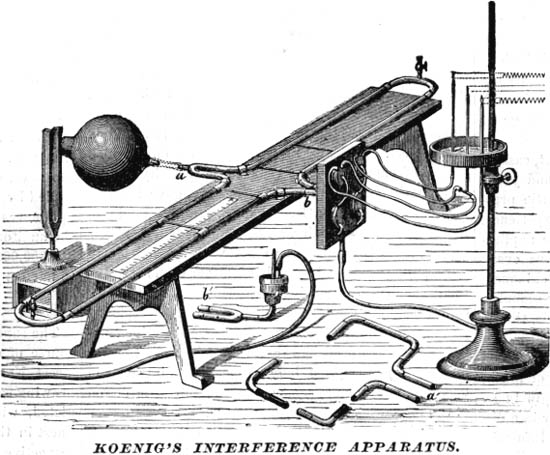

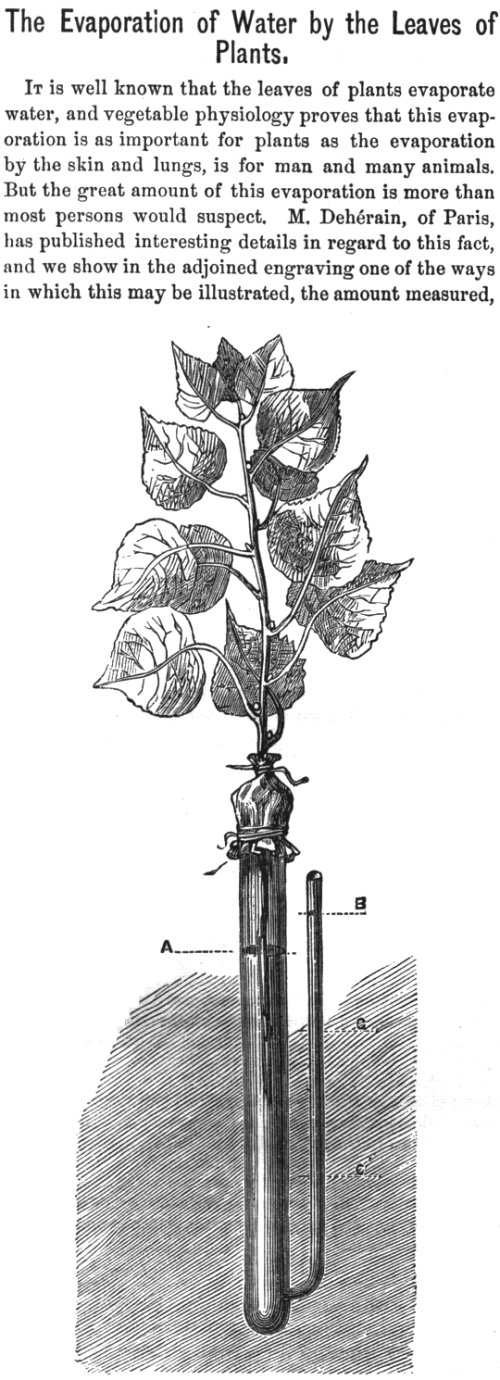

Below: a sampling of images from this volume of The Manufacturer and Builder: