Canonical Inventor

Today, canonical inventor. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

For years I've struggled to understand our hero of invention. Now I think that person is finally beginning making sense to me. Watt never claimed to've invented the steam engine nor Fulton the steamboat. So why are they emblazoned upon our history books? I've come to believe that it's about tipping points.

Inventors invent because they have to. But a hero appears during any groundswell in human desire -- the desire for power to aug-ment our bodies, desire to travel rapidly, desire for access to information, desire to lighten darkness -- the desire to fly.

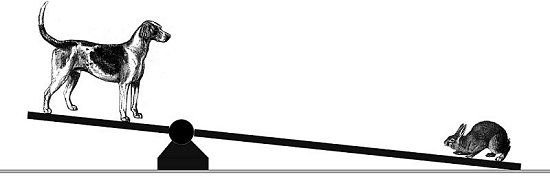

Each of our nominal heroes of invention worked to satisfy one those desires, yet not one of their canonical inventions was embryonic -- each had existed in earlier forms. Still some common quality led to beatification as a hero. What was it? As we trace the invention of the light bulb, the airplane, or the telephone, we find each was buoyed both by communal desire and by recent nearly-successful attempts to create them. Each rode a cresting wave.

The technology that our hero inventor brings to fruition is in-variably one that we'd all wanted, and had partially conceived. It was one with which other inventors had teased us. The hero's contribution was, in that sense, no invention at all.

Yet three distinct qualities mark our canonical inventor. Two of those qualities are a powerful sensitivity to communal desire and an internal drive that few of us ever muster. The third -- and this may seem to contradict what I've been saying -- is unparalleled inventive genius.

The Wright Brothers did not invent the airplane. Even encyclopedias were talking about heavier than air flying machines before the Wrights built theirs. But the Wrights did invent a propeller with an airfoil cross-section, a workable control system, an airworthy configuration, an aluminum engine, and much more.

So here comes the notion of a tipping point: By 1903, the airplane would be invented -- very soon. Orville Wright had a near-fatal bout with typhoid fever in 1896. If it had killed him, a different airplane would've been made first -- maybe by Santos Dumont or Glen Curtiss. The airplane's time had come. The technology was ripe and ready to fall. Others knew that as well as the Wrights did; oth-ers had comparable determination and creative genius.

As I think about this moment in history, this tipping point, this apple about to fall into the lap of one great inventor or an-other, I think of words that T. S. Eliot put into the mouth of Thomas Becket: "I would no longer be denied; all things proceed to a joyful consummation." That sense of destiny wreathes the lives of those few inventors who, though not really first, were pivotal.

So grant Morse his telegraph. Grant Prometheus his fire. Give Lindbergh his Flight and let Yogi Berra have the crown for the poetic deconstruction of English. No matter that none was first. Each did what he did very well indeed, and at the right moment in history.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

For more on the notion of a tipping point, see M. Gladwell, The Tipping Point : How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. (Boston: Back Bay Books, 2002).

These ideas about canonical inventors are discussed at greater length in J. H. Lienhard, How Invention Begins: Echoes of Old Voices in the Rise of New Machines. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006): Chapter 14.