Of Organs and Engines

Today, organs and engines. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

After the late 1700s, the industrialization of Europe included the industrialization of music. Violin necks were extended and gut strings were replaced with metal. The new industrial-strength violin joined with other souped-up instruments -- pianos with heavy iron frames, French horns with valves like those on Watt's engines. Pitches rose, musical textures became denser. The or-chestra itself became a new industrial engine.

If organ builders lagged other instrument makers, they made up for it in relentlessness. Air pressures rose inexorably. A bewildering array of valves, linkages, pipes, and air-chests, all conspired to make a dazzling beast of the late Romantic organ.

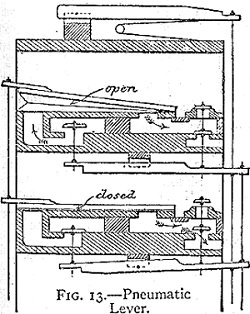

One development was the Barker-lever. People debate whether Charles Barker or David Hamilton invented it. But the British Barker worked with French organ builder Cavaille-Coll who truly capitalized upon this remarkable device during the 1840s.

One development was the Barker-lever. People debate whether Charles Barker or David Hamilton invented it. But the British Barker worked with French organ builder Cavaille-Coll who truly capitalized upon this remarkable device during the 1840s.

The Barker-lever solved a rising crisis now facing organists. The sheer mass of connecting machinery within the organically growing organs had increased until human hands were no longer strong enough to play them.

Actually two machines had posed that same problem. Just as it finally took too long to press down an organ key, it also took too long to open the valves of a new fast-moving high-pressure steam engine. Then, suddenly, the same solution arose for both problems.

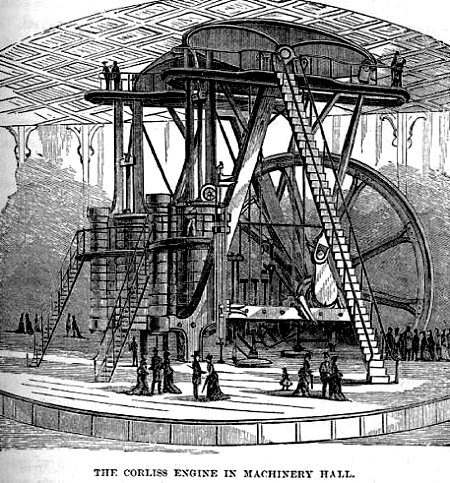

The trick in either case was to trigger a device that would augment the movement. George Corliss patented a dashpot system that gave remarkably crisp valve action and better steam engine efficiency. The Barker-lever used the same sort of small pressure chamber to augment the hand -- to make organs respond instantly to a finger upon a keyboard.

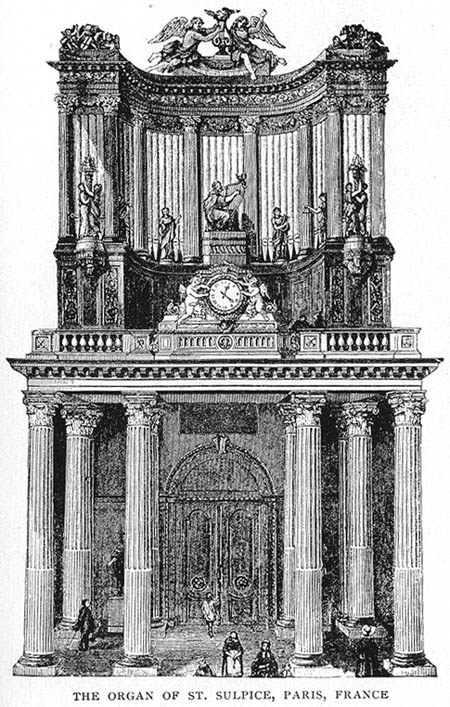

So, the centerpiece of the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition was a 70-foot-tall monster Corliss engine. People came from miles simply to gawk at the spidery action of its valves. A scant fourteen years earlier, Cavaille-Coll had installed the largest of his organs in St. Sulpice Church in Paris. People came from miles to hear -- and to gawk at -- it, as well.

Cavaille-Coll's great organ and Corliss's great engine were emblems of their age. And, of course, both needed to be bridled. These supercharged organs educed a new school of highly trained virtuoso organists. And a school of French composers arose along with them. They forged true music from what might have degenerated into mere raw sound.

Starting with Cesar Frank, and continuing through such composer/organists as Widor, Vierne, Dupre, and Messiean, they wove a special, mystical, vision. That vision was machine-driven, but machine-driven visions are what define you and me. They are the stuff of all art, all function, and of our human species, as well. But that is another subject for another day.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

P. Williams, Organ. The New Grove Dictionary of Music & Musicians.(Stanley Sadie, ed.) Vol. 13, New York: Macmillan, 1995, pp. 710-779.

My thanks to organist/librarian Edward Lukasek, University of Houston Libraries, for suggesting the topic and for his invaluable counsel.

This material originated in comments that I made for a concert by virtuoso organists Robert Bates, Matthew Dirst, and Clyde Halloway: "The Three Organists -- A Pipe Organ Extravaganza" Grace Presbyterian Church, February 12, 2005.

Here a site that tells about George Corliss's engines:

http://www.vintagesaws.com/library/steam/steam.html

This is large site deals with Aristide Cavaille-Coll:

Aristide Cavaillé-Coll - Wikipedia

The organ music in the audio track is from Piece Heroeque, by Cesar Frank. It is played by Marie-Claire Alain on the Cavaille-Coll organ in the Church of St. Francois de Sales, in Lyon, France. ERATO ECD 88110.

Image sources: The Barker (pneumatic) lever in text is from the article on organs in the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica. The St. Sulpice organ image is from Lahee, The Organ and its Masters, 1902. And the Corliss engine is from a period article about the 1876 exhibition (source unknown).