Baghdad Batteries

Today, electricity in the ancient world? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The past has an infuriating way of revealing itself in tiny eye-blinks. That's why history is such frustrating fun for those who take it up. A line in a teenage letter by some famous person might mean nothing. But if we have very few letters, it looms large. It may be terribly misleading, but it cannot be ignored.

Take the case of the Baghdad Batteries - a sort of technological teenage letter from a remote past. The Baghdad Batteries are an archaeological relic found in a village near Baghdad in 1936. They are five-inch-tall, not-terribly-interesting clay jars.

Two years later, German archaeologist Wilhelm König noticed them in the Baghdad Museum. When he looked closely, he was astonished. He went on to publish a paper pointing out that they could have been batteries used for electroplating. And he dated these batteries from the third century BC.

Within the jars was a vertical iron rod, surrounded by a copper cylinder. The iron and the copper were mounted in an asphalt stopper that insulated them from one another. Fill the jars with an electrolyte -- like, say, vinegar -- and a voltage difference will be generated between the copper and iron.

So these jars definitely could have functioned as electric batteries. Naturally, people began embroidering on König's analysis. One widely circulated idea was that the Egyptians used them to power electric lights as they built the interior of their pyramids. Never mind that the pyramids were built over two thousand years earlier, and before anyone had worked with iron.

In 1948, a GE engineer replicated these jars, filled them with vinegar, and measured an output of almost two volts. But their maximum current was pitifully small. At best they delivered about a fortieth of the power of a triple-A battery. Later, a German scientist found that, by using a very large number of them, he could electroplate a very thin layer of gold on silver.

More problems arise: We find no wires; how did people collect the power output? We find no written record of such devices. And the hard asphalt seal would have to be broken every time the electrolyte was replenished. (Think about refilling car batteries.)

Yet, as claims for these batteries shrink, their validity increases. If these were batteries, we need to remove modern electrical systems from our thinking. They could've been used for healing. The Greeks and Romans were known to combat the pain of gout by standing patients upon electrical eels until their feet became numb. Or the batteries might've served a theatrical purpose, like making a metal statue tingle when you touched it.

Two things strike me as I read about the Baghdad Batteries. One is that we need to bridle our enthusiasm as we read the record of history. But the other is that history does indeed hold the capacity for handing us astonishing surprises.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

My sources for this information are all web-based. See, e.g.,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baghdad_Battery

or http://www.unmuseum.org/bbattery.htm .

By the way, a biologist wrote (some time after this first aired) to point out that electric eels don't live outside the Amazon basin. Thus my sources had to've been wrong in saying the Romans used them to administer shocks. I expect they used some other sort of electric fish.

And this site shows how you might make your own Baghdad Battery.

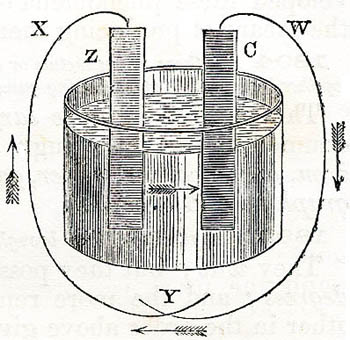

An elementary battery shown in Wells' Science of Common Things, 1857

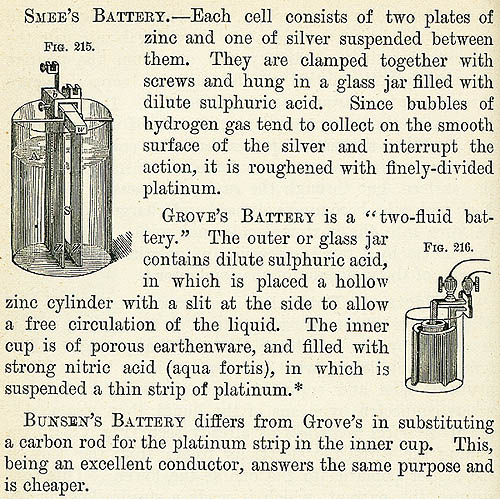

Three early batteries as shown in Steel's Fourteen Weeks in Physics, 1878.

All four of the batteries shown above are close kin to the Baghdad Batteries.