Lobster Shells

John H. Lienhard presents guest Andrew Boyd

Today, guest scientist Andrew Boyd asks where lobsters come from. The University of Houston' presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

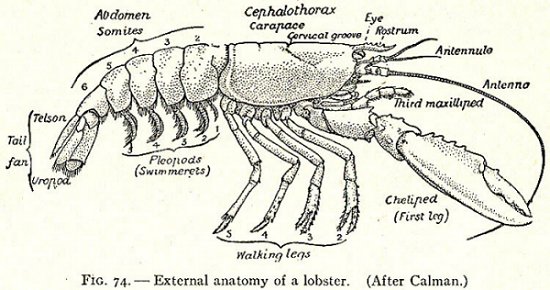

Lobsters are arthropods, a category that includes ants, spiders, scorpions, and even cockroaches. They are close cousins of the annelids, or segmented worms, a key difference being that arthropods have a hard shell. Though it covers the outside of the body, the shell serves much the same function as our internal skeleton. In the case of lobsters, it also provides protection from other sea creatures in search of a succulent meal.

The problem with a shell is that it can't grow, so the lobster must periodically shed it and start a new one. The process, known as molting, is dangerous, and one of nature's many engineering marvels.

Trevor Corson explains the process in a wonderfully written essay entitled "Stalking the American Lobster." Molting begins as the lobster's gelatinous body expels water, causing it to shrink. As the shell splits open, the lobster shuts down its twenty sets of gills and begins freeing itself from its former encasement. The lobster has about an hour to complete the task before suffocating, and will sacrifice body parts if necessary. Claws can be especially difficult to remove through the narrow opening that connects them to the main body.

Once the lobster is free, and the gills are functioning, the body swells; and for the next five hours the lobster secretes the beginnings of a new shell that will harden over the coming weeks. During this period the lobster is at heightened risk from hungry predators, and does its best to hide. The old shell is an excellent source of minerals, and the lobster will use it as a food source while waiting for the new shell to form.

Molting also plays an important part in the lobster's reproductive cycle, since female lobsters can only become pregnant when free of their shells. Mating begins well in advance of molting, as males and females participate in courtship rituals. When the female is ready to mate, she will place her claws on the chosen male's head in a process known as "knighting." There is speculation that she uses this opportunity to secrete a hormone that reduces her partner's aggressive tendencies, which include cannibalism.

Aggression is not limited to males, as females suffer from what researcher Diane Cowen calls PMS, or pre-molt syndrome. According to Cowen, "Before they molt, [females] have an activity peak and can go a little berserk." Other females may be the target of attacks as the pre-molting female prepares to join her companion.

Pregnancy may last up to twenty months, and may produce anywhere from ten to one hundred thousand offspring, depending on the size and maturity of the mother. Female lobsters have the ability to retain a male's sperm for several years, and to undergo a second pregnancy without the need for mating. When a Maine lobsterman finds a pregnant female, he will mark her for other lobstermen -- a sign that she is too vulnerable, too important, to be harmed. Indeed, lobstermen treat pregnant females with an almost mystical reverence.

I'm Andy Boyd, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

An updated version of this episode can be found at 3094.

Dr. Andrew Boyd is Chief Scientist and Senior Vice President at PROS, a provider of pricing and revenue optimization solutions. Dr. Boyd received his A.B. with Honors at Oberlin College with majors in Mathematics and Economics in 1981, and his Ph.D. in Operations Research from MIT in 1987. Prior to joining PROS, he enjoyed a successful ten year career as a university professor.

The material in this essay is taken from "Stalking the American Lobster," by Trevor Corson, which originally appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in April of 2002, and was reprinted in The Best American Science Writing 2003, editor Oliver Sacks, series editor Jesse Cohen, and published by HarperCollins, 2003.

The following Illustrations are (above) from R. W. Hegner, Practical Zoology. New York: The MacMillan Co., 1917, pg. 131. And (below) from J. G. Wood, Animate Creation; Popular edition of "Our Living World," A Natural History. Vol. VI, New York: Selmar Hess, 1898, pg 464 facing.

For a larger image, click on the picture above.