Riding the Wrong Horse

Today, we ride the wrong horse. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

1893 was quite a year. We'd had been at peace for some time, and we were flexing our creative muscle. My father was born that year. So too was Thomas Edison's first motion picture studio, the Black Maria. It was a black shed, open to the sun and mounted on a pivot so it could be constantly turned to catch the best light. Out of it came his first movie, The Record of a Sneeze. And that's all it was -- a brief scene of a man sneezing.

Edison had just patented his Kinetograph (for photographing a series of images) and his Kinetoscope (which allowed a viewer to watch the flickering images through a peephole). Then others began developing machines to project those images on a screen. And we've all gone to the movies ever since.

But now I find a new wrinkle. While all this was going on, photographer Alexander Black was developing a so-called picture play. It came out the same year as The Sneeze. The title was Miss Jerry, and I learned about it from an 1896 Scribner's Magazine article by Black. When I first saw the article, it took me a moment to understand what it was about.

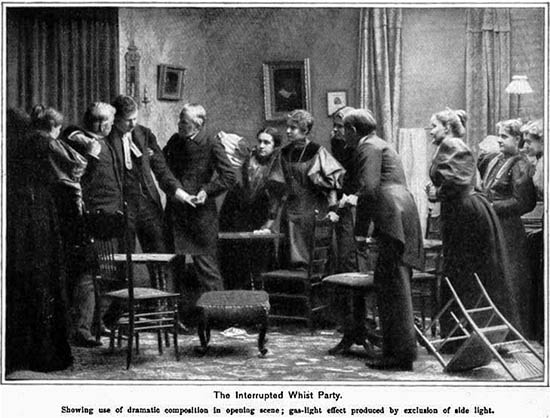

Black tells how he used his camera to produce plays. He made fine pictures, no grainy sequence of a man sneezing, here. Then he arranged sequential tableaux of scenes from the play. These were to be projected at a rate of around four per minute, by a magic lantern. A narrator meanwhile told their story.

Black made no attempt to create any illusion of motion. Yet he did provide sequential movement through the play's action. The result was a lot closer to our movies today than Edison's Sneeze was. Black dealt with real actors and real stagecraft. He talks about the problem of directing a play so as to capture the unfolding dramatic content without the intervening motion.

And yet, as Black finished his article, we were moving from that peepshow of a sneeze, to projected movies of far more exciting stuff -- a kiss, a belly dance, a prize fight. In one movie about The Execution of Queen Mary, Edison created an early special effect by stopping the camera long enough to sever the queen's head.

So Black is forced to add these somewhat defensive words:

Pending the perfection of the [new moving pictures], the ordinary camera [still] gives freest expression to the processes of the picture play.

Then he adds a really prophetic remark. He says, With whatever medium, [we shall still find] problems in the storytelling. If you love the movies as I do, you know that sad truth lingers.

By then Black knew he'd chosen the wrong horse in 1893. But I look at his lovely photos and wish I could watch one of his picture plays. Of course we all feel that way about so many of yesterday's short-lived technologies. Oh to ride a Zeppelin, a Panama Clipper or a Clipper Ship. Wouldn't it've been something to've experienced the first five days on the maiden voyage of the unsinkable Titanic!

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

A. Black, The Camera and the Comedy. Scribner's Magazine, Vol. XX, No. 3, November, 1896, pp. 605-610.

The full text of Black's 1896 comment, without the ellipses I used on air, goes as follows:

Pending the perfection of the vitascope, the cinematograph, and kindred devices, the ordinary camera, in partnership with the rapidly dissolving stereopticon, gives freest expression to the processes of the picture play, not only for a greater clearness and steadiness in pictorial result, but because of the wider range of selection possible to the portable camera. And, with whatever medium, we find, as I have suggested, problems in the story-telling function that is imposed upon the pictures.

A scene from Alexander Black's picture play, Miss Jerry, "The Interrupted Whist Party"