Dolly Shepherd

Today, three women parachutists. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Molly Sedgwick turned 83 in 2003. To celebrate, she scheduled a parachute jump. She had a very compelling reason for doing so. This was not just her birthday, it was also the ninety-fifth anniversary of an event in the life of her mother, Elizabeth Shepherd.

Our story begins in 1903 -- same year the Wright Brothers flew. Buffalo Bill Cody took his Wild West Show to London where he had trouble. When he put on a blindfold to shoot a plaster egg from his wife's head, the bullet creased her scalp. But then, sixteen-year-old Shepherd volunteered to take her place.

The next year, Cody expressed his thanks by taking Shepherd to Auguste Gaudron's aerial workshop. After a scant thirty minutes of instruction, Shepherd, now using the new stage name of Dolly, began doing exhibition parachute jumps from so-called smoke balloons.

Parachuting was already a century old -- a strictly exhibition game, still primitive and dangerous. Dolly Shepherd's nerve and flair made her the star of the show. She saw her first fatality when one girl landed on a factory roof, and her parachute dragged her over the edge. Others died, and

Dolly had several close calls.

In a typical jump, two girls got ready. They vented their balloon so it would start down; and then they jumped. The event her daughter was celebrating in 2003 was one in which the other girl's parachute had tangled. With remarkable calm under pressure, Dolly got the girl out of her harness, told her to wrap her arms and legs around her own body, and together they made the first tandem parachute jump -- from an altitude of 11,000 feet.

They landed hard, and Dolly Shepherd took the brunt of the impact. She was paralyzed by the blow. A doctor, who obviously thought like a barnstormer, tried subjecting her to massive elec-tric shock. That was not accepted therapy -- then or now -- but her luck held. By some means, the shock unlocked her paralysis.

And, while she was recovering, her mother secretly jumped in her place. When Dolly went back to work, she jumped for another four years. Then, one day as she prepared to jump, she thought she heard a voice saying, "Don't come up again or you'll be killed." So she gave it up. Two years later she joined the war in France as a driver mechanic.

She also survived that, and she lived to the age of 96. She lived to see a man on the moon and a rocket circling Saturn. Dolly Shepherd lived to see women stepping off the face of the earth in rockets -- just as primitive and new as the parachutes she'd used, when she stepped off into the sky eighty years before.

Then, her daughter Molly became a third-generation parachutist. No wonder Molly felt driven to celebrate her mother's remark-able act of courage on her own 83rd birthday. A wonderful thing, really -- this woman asserting her history as we finally prepare to conquer, not just the sky, but the reaches of space as well.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Lomax, J., Women of the Air. New York: Ballantine Books, 1987.

For more on early parachuting, see Episode 1316.

This is a greatly reworked version of Episode 234.

For more on Dolly Shepherd see the Wikipedia article about her.

Dolly Shepherd

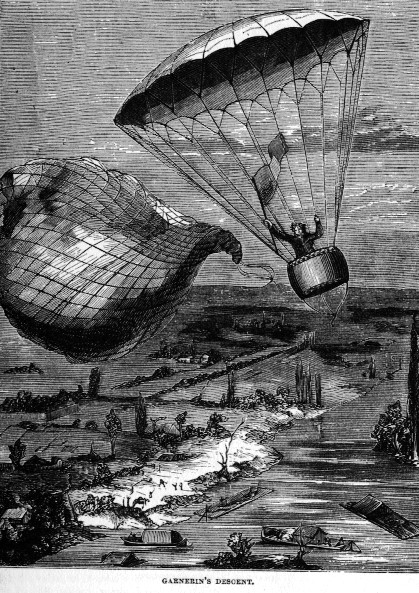

The first parachute, that of André Garnerin, in 1797. Left: the parachute is being carried up by a balloon. Right: it carrying a person safely back to earth (Images from the 1897 Encyclopaedia Britannica)

From Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1869

A mid-nineteenth century impression of Garnerin parachuting from a balloon.