Alexis Carrel

Today, a president killed, and a Nobel Prize given. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The president of France, Sadi Carnot, was fatally stabbed by an anarchist in 1894. (By the way, the Sadi Carnot who helped set the foundations of thermodynamics was the president's uncle. But, like his uncle, the president had also been educated as an engineer at the École Polytechnique in Paris.)

In any case, the vein leading to President Carnot's liver had been severed, and he bled to death in the hospital. But a young medical student in Lyon, Alexis Carrel -- just shy of his twenty-first birthday -- realized what this meant.

At the time, no one was able to do anything so delicate as suturing a vein. But Lyon happened to be the silk capital of France, and Carrel went to an expert. She was Madame Leroidier, a silk embroiderer. She taught him the use of tiny needles and fine thread. Carrel developed a delicate technique for sewing severed vessels together in such a way that blood inside would never touch thread.

Dr. Nicholas Tilney tells us how this discovery played out. It was the first step toward transplanting organs. Carrel and oth-ers soon applied his suturing technique to transplants and, eight-een years after Carnot was stabbed, Carrel won the Nobel Prize for his work in transplantation.

Hopes for doing radical surgical experimentation were slim in rural France, so Carrel moved to Chicago in 1904 to work with a doctor Charles Guthrie. There they carried out some real Isle-of-Doctor-Moreau-style experiments -- like transferring the head of one dog to the body of another. Of course they were simultaneously perfecting techniques for transplanting kidneys and other human organs. But Guthrie grew fed up with Carrel's zeal for self-promotion and they fell out in 1908.

Carrel moved to the Rockefeller Institute in New York. One photograph from New York shows Carrel with two greyhounds -- one black, the other tan. The black dog has one tan leg, and the tan one, a black leg! Very dramatic, but routine kidney transplants would remain out of Carrel's reach until after his death in 1944.

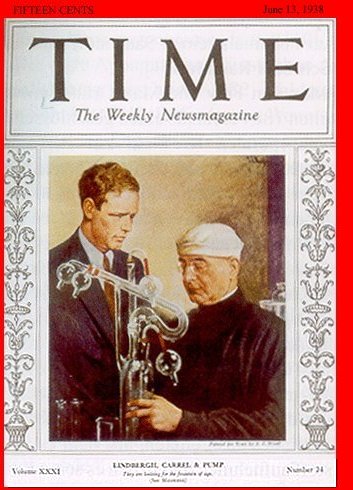

One lingering problem was supplying blood while a transplant procedure halted its normal flow. Charles Lindbergh heard about that, and he devised a pump to circulate blood without doing serious damage to it. In 1938 the famous pair, Lindbergh and Carrel, were displayed with the pump on the cover of Time Magazine.

Today, that photo carries sinister overtones. Lindbergh was then far too friendly with the Nazis, and Carrel was openly sympathetic. When WW-II began, Carrel went back to the collaborationist Vichy government in France. He became Director of something with the ominous name, Foundation for the Study of Human Problems.

Carrel died of a heart attack in the last days of that evil empire. And, if you've survived kidney failure, I expect you'd rather remember him as one reason that you're alive and well today.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

N. L. Tilney, Transplant: From Myth to Reality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003.

For more on Alexis Carrel, click here.

And for more on Lindbergh's contributions, see:

http://www.charleslindbergh.com/history/nelson.asp

The father of both thermodynamicist Sadi Carnot and the prime minister's father, was mathematician Lazare Carnot. (He turns out to have been a member of the ruling body of France in the period between the Reign of Terror and the rise of Napoleon.)

I am grateful to Sarah Fishman, UH History Department, and Rob Zaretsky, UH Honors College for very helpful counsel on this episode.