Fine Press Incunabula

Today, the most beautiful book -- but so what? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

How often have you heard on the history channel that the printing press created the Renaissance? It's trite but true. And yet collectors of rare books are very apt to distort that fact.

Some twenty million individual books were printed in the 45 years between Gutenberg and the beginning of the sixteenth century. Many of those books still exist; some are in very shabby condition.

For a book to've survived, and to be attractive to a collector, two things had to be true of it. First, it had to've been one of the beautifully-made books. And, as with any very popular product -- computer, TV set, automobile -- many shabby books were in-evitably printed for every beautiful one.

The second factor that augurs for the survival of an old book was being not-too-interesting. The highly-prized old books are very often those that people did not often take down from the shelf and handle.

I recently became curious about one of the more famous early printed books -- one of the best-known of these had a pretty imposing title: the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. It was printed by an Italian, Aldus Manutius. He was a court intellectual, whom the royalty set up as printer in 1495.

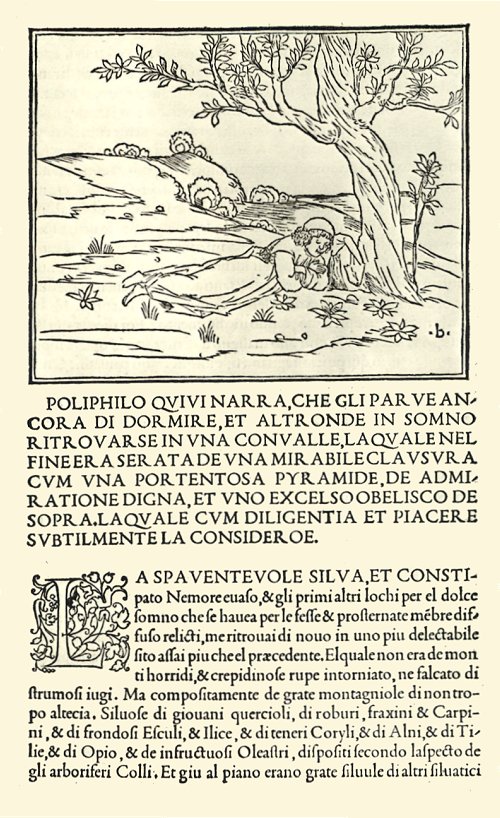

The investment paid off -- sort of. Manutius printed some gorgeous books. And most gorgeous of all was his Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. The contents were another matter. It's usually attributed to a contemporary writer named Francesco Colonna. But it well could've been someone else. And scholars debate his intentions.

It reads like a fantasia and an architectural travelogue. Poet John Tranter says he quickly tired of trying to read it. He describes it: A man named Poliphilo goes, in a dream, with his love Polia to await Cupid at a ruined temple by the sea. Polia entices him inside to admire the antiquities. Endless descriptions of dream-art and fantasy-architecture follow, interspersed with brief episodes of fondling and heavy breathing. Tranter calls it detailed, obsessive, and fetishistic.

So, if the new medium of print created the Renaissance, this book played a very limited role. It was in the cheap stuff that print truly altered life on planet Earth -- hastily printed copies of the Boccaccio tempting common folk to learn the skill of reading -- cheap Bibles in local languages.

And, of course, that's where we are today. The Internet is into very similar mischief. You can find beautiful web sites, just as the Renaissance produced beautiful books. We pause to admire them, but then we quickly move on to E-bay or Google. Printing did not achieve greatness with a few fine coffee table books, but by fulfilling a far more primal function. It seized people's minds with readily available knowledge in every form -- with the elixir of knowing what they previously could not know.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Click here for a detailed description of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, see: http://mitpress.mit.edu/e-books/HP/hypsinop.htm

A Page of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, printed by Aldus Manutius in 1499.