Fourier

Today, we meet the last great 18th-century genius. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The 18th century radiated a peculiar kind of genius. It gave us people like Mozart, Jefferson, Euler, and Ben Franklin. Isaac Newton led us into the astonishing 18th century, and Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier led us out of it.

If you've ever studied mathematics, heat flow, or acoustics, you've heard of Fourier. The man himself was born in France in 1768. He was trained in mathematics and military engineering. Then he was caught up in the politics of the French Revolution. He was a revolutionary, but other revolutionaries jailed him when he defended victims of the Reign of Terror.

In 1795, Fourier, now 27, took a faculty post at the new Ecole Polytechnique. But politics followed him, and he was jailed again. A colleague finally took him out of harm's way by finding him a foreign post with a general even younger than he was. In 1798, Fourier went off to Egypt with -- Napoleon Bonaparte.

Napoleon made Fourier the secretary of the newly formed Institute of Egypt. Fourier did all sorts of negotiation and administration during the Egypt campaign. When Napoleon returned as the leader of France, he sent Fourier to Grenoble as the Prefect of Isère -- something like a state governor here.

Fourier went to work with astonishing energy. He built roads, he engineered a large land-drainage program, he wrote papers on mechanics and a book on Egypt -- and he was made a baron. He finally resigned the post in 1815 to avoid being entangled in Napoleon's abortive return from exile. He went back to full-time research.

Fourier had started thinking about heat flow in Egypt. While he was in Isère, he submitted a paper on the analytical theory of heat to the Academy of Science. In it he showed how to describe heat flow in solid bodies. But he did much more than that. He also created a form of mathematics that let engineers and scientists solve problems that had previously been unthinkable.

Like most real masterpieces, the paper broke rules. Fourier's intuition led him where his logic couldn't always follow. The work offended many great mathematicians, and for 15 years he fought to get it published. It didn't come out until 1822. By then it was a full book and the most important mathematical work of his age.

The Egypt adventure touched Fourier's entire life. It began a lifelong obsession with heat and with the healing powers of heat. In his later years he swathed himself, mummy-like, in his overheated Paris apartment. At the end, he died of a chronic illness he'd contracted in Egypt. But by then Fourier's work had permanently expanded the very character of engineering.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Fourier, J., The Analytical Theory of Heat (transl. by A. Free man). New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1955.

Gratton-Guiness, I., Joseph Fourier 1768-1830 (With J.R. Ravetz). Cambridge: MIT Press, 1979.

Joseph Fourier Savant et Préfet 1768-1830, Grenoble: Bibliotheques Municipales, 1989. (no author given)

This episode has been greatly revised as Episode 1878.

Joseph Fourier

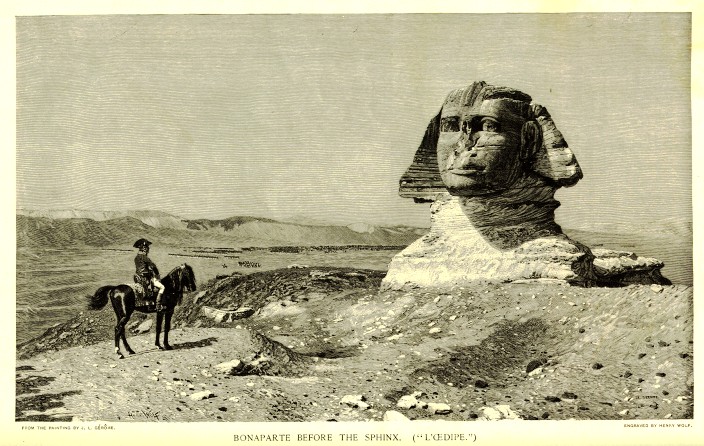

Napoleon shown contemplating the Sphinx in the 1895 Century Magazine.