Justus Liebig

Today, we create the first research laboratory. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Long ago I wrote a master's thesis on the properties of a chemical called aniline. It was an exciting time for me. I'd never heard of aniline, but I learned that it was a standard dye base, and that it might make a good rocket fuel. I also had to learn how to find data in a German periodical called Liebig's Annals of Chemistry. Twenty years later I found out the remarkable way Liebig's life was interwoven with the aniline I was studying.

Baron Justus von Liebig was born in Darmstadt in 1803. He took up chemistry when he was seventeen. When he was twenty, he went to Paris for a year to study with the famous French chemist Gay-Lussac. Gay-Lussac opened his eyes to the new idea that accurate experiments were needed to make sense of chemistry.

Liebig came back to a post at the University of Giessen in Germany. There he turned his young man's enthusiasm on the idea of precise experiments. He worked single-mindedly to set up a chemical research laboratory. He had to spend his own salary on equipment. But by 1827 Liebig had a 20-man operation, the likes of which the world hadn't seen before.

Liebig is honored for his work in organic, pharmacological, and agricultural chemistry. But this laboratory was his greatest contribution. Other chemists had to copy it to keep up with him. It was the first systematic research laboratory, and it changed our thinking. Before Liebig, research was an amateur's game. Now it was being put into the hands of a new breed of professionals.

But there's more to the story. In 1843, one of Liebig's former students sent him an oil he'd isolated from coal tar. Liebig's lab found a compound in it that reacted with nitric acid to make brilliant blue, yellow, and scarlet coloring agents. It was a compound Liebig had already anticipated -- a form of benzene with one hydrogen atom replaced by an amino group. They called it aniline.

By 1860 Germany had created a new dye industry based on aniline. That dye industry, in turn, carried Germany into world leadership in industrial chemistry. This leadership owed a lot to Liebig's ideas about chemistry. But it owed even more to his vision of systematic research, invention, and development. While the Germans were setting up their dye industry, Edison and others were setting up their own version of Liebig's laboratory here in the United States. You and I know full well what a profound impact R & D labs have had on American life.

And it was all born of youthful energy. Our very concept of systematic research was born when a teacher -- the great chemist Gay-Lussac -- struck a chord in his 20-year-old student, Justus Liebig.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Holmes, F. L., Liebig, Justus von. Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 8, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973, pp. 329-350.

The Liebig Museum in Giessen maintains an excellent website with more on Liebig and the history of his laboratory.

This episode has been revised as Episode 1652.

(From an obituary ca. 1873, source unknown)

The Baron Justus von Liebig

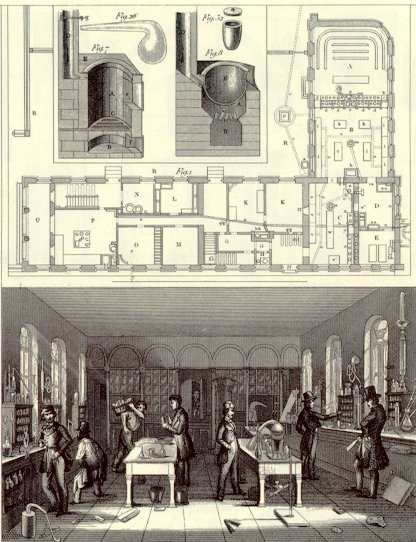

An old engraving of Liebig's lab and its floor plan