Museum of Printing History

Today, we visit a printing museum. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Since last Saturday, the ancient problem of displaying the written word has lain upon my mind. I visited Houston's Museum of Printing History, and I realize that, for all I've said about papyrus and paper, parchment and stone, writing and printing — I'd never quite seen the full sweep of the subject in one place.

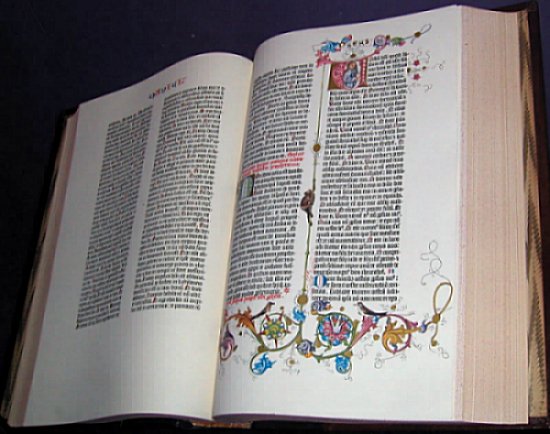

Consider the difficulty: The Rosetta Stone may be seen only in the British Museum. Gutenberg's press has long since perished. Only 48 Gutenberg Bibles survive today and, when they change hands, they do so for millions of dollars. So this museum enriches a fine collection of original material with exquisite facsimiles of the unattainable treasures. Their Rosetta Stone is not just a copy, but a casting of the original.

Their Gutenberg press is a great hulking wooden machine made by the Pratt Wagon Works in Utah. That may seem unlikely but who'd be better qualified to build this large wooden structure? The design is based on a woodcut of a later press that historians deem to be very close to the original. And the Gutenberg Bible is a faithful reproduction, a thousand copies of which were printed in 1961.

Printing is, of course, far older than Gutenberg. We see an original eighth-century block-printed Japanese scroll. It predates Gutenberg's development of movable metal type by eight centuries. In fact, this scroll was printed three centuries before the Chinese first invented printing with movable ceramic type.

Perhaps the museum's strongest focus is on the machinery of printing. Here are the small letterpresses that've been used to print fancy invitations as well as to foment revolutions. You see early power presses, and the first offset printing press. I'm drawn to the Linotype machine, because I know how it revolutionized newspaper printing. Using it, you could finally set type from a keyboard, instead of having to pick each letter out of a case.

The late-eighteenth-century invention of lithography is well represented. It radically changed nineteenth-century newspapers when it gave them effective means for including pictures.

I pause in one of the museum's many workshops. Charles Criner, a fine artist and a student of John Biggers, is continuing Biggers work with powerful lithographs of the Black American experience. We chat as he creates art, right before my eyes.

The museum dances between process and content. On the walls, we read pages printed by Benjamin Franklin, newspapers from Colonial times, the War for Texas Independence, the Civil War --. We see pages printed in Mexico, almost a century before the Plymouth Colony. Originals where possible and facsimiles where not -- a room for making paper and another for setting type.

It's all there, the whole sweep. A work in progress. A soul-settling adventure, from which to emerge into the slanting light of the autumn afternoon, here in Houston.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

For information about Houston's Museum of Printing History, see: http://www.printingmuseum.org/

I am most grateful to Betsy Griffin, Executive Director of the Museum of Printing History for her counsel, and to Oscar Graham of Houston's Detering Book Gallery for suggesting the topic.

(Be sure to click on the links above for more pictures.)

Fine facsimile of Gutenberg's Biblia Sacra, Patterson, NJ: Pageant Books

(This is one of the 1000 copies of this two volume set that were printed in 1961.)