Who Are We?

Today, who are we? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We all weigh the question, "Who am I," now and then; but the place we hope to find the answer shifts. I long ago despaired of finding a usable answer in autobiographical data. For a while, I thought it might be a matter of self-perception. Then I read Oscar Wilde's wonderful quip, "Only the shallow know themselves."

Now I'm reading a pamphlet by Maya Pines: Inside the Cell. Maybe objective science will tell me as much as the subjective stuff will. Whatever else we might be, we certainly are great gaggles of cells. So let's see what they have to tell us:

Robert Hooke's book on the compound microscope, Micrographia, came out in 1665. In it, he sketched the microstructure of a slice of cork. Then he wrote, "I could ... plainly perceive it to be all perforated and porous, much like a Honey-comb, but ... the pores of it were not regular." Of course he was seeing the walls of dead cells in dead bark. They'd once been filled with fluid, and alive.

Not until 1838 did a German botanist compare notes with a zoologist. They realized the structures they'd been studying in plants and in animals were very similar, and they concluded that all living things are made up of cells.

Twenty years later, it became clear that cells are the home of disease as well as life. But cells remained perplexing because they take on such a dizzying variety of forms. And they execute so many functions. Still, they all have certain basic elements: They have a very thin outer membrane. It holds a liquid called protoplasm. (That word came from the theological term, protoplast. It once referred to Adam as the first formed being.)

Also, with one exception, cells have a nucleus. Pines calls it the cell's command center. The exception is our red cells. They're formed in bone marrow, they cannot reproduce, and they serve only as carrying cases for hemoglobin. And hemoglobin, in turn, transports oxygen throughout our bodies.

Pines presents a remarkable chart showing the range of things that can be called cells. The largest is a six-inch ostrich egg. A human egg is only a 250th of an inch in diameter. Those red cells are less than one millionth of an inch.

But they all include nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, water, and salts. They all include DNA. There's even some in our red cells. Uncoil each long molecular helix of DNA in your body, lay them end-to-end, and your DNA will reach all the way to the sun and back.

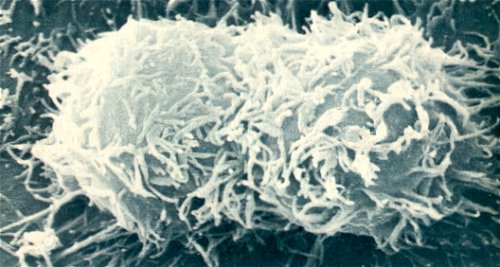

Electron microscope pictures show human cells girdled by an outer mess of microfilaments to help them crawl. What frightful-looking creatures! Yet there I am -- there you are: splatters of organic matter, marvelously efficient, crammed with complex apparatus -- mitochondria, ribosomes, lysosomes -- more than we'll ever fully understand.

How right Oscar Wilde was! We would be shallow indeed to think that we truly knew ourselves.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

M. Pines, Inside the Cell: The New Frontier of Medical Science. U.S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1978.

You'll find a huge amount of information on cells and cell structure on the web. I won't even try to list it all. For more on Hooke and his microscope, see: http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/hooke.html.

I am grateful to Lewis Wheeler, UH Mechanical Engineering Dept., for suggesting the topic and for his counsel.

The real me! Electron microscope picture of a human cell beginning mitosis, or reproductive division. (from Pine's pamphlet.)