Foghorns and Sirens

Today, we make noise. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1867, the first primitive steam-powered fog siren was installed at the lighthouse on Sandy Hook, New Jersey. Sandy Hook reaches out almost halfway across New York Bay toward Brooklyn, and it poses a serious threat to shipping in and out of New York City.

The light served warning when it could be seen. But, in fog, Sandy Hook could not be seen. It had to be heard; and this new machine was very audible. Previously, ships were warned off the rocks by repeated cannon fire. That became hopelessly expensive and inconvenient as shipping trade increased.

The light served warning when it could be seen. But, in fog, Sandy Hook could not be seen. It had to be heard; and this new machine was very audible. Previously, ships were warned off the rocks by repeated cannon fire. That became hopelessly expensive and inconvenient as shipping trade increased.

Historian Michael Lamm tells how, five years after that first installation, the Sandy Hook Lighthouse acquired one of the new steam sirens just patented by the Brown Brothers in New York.

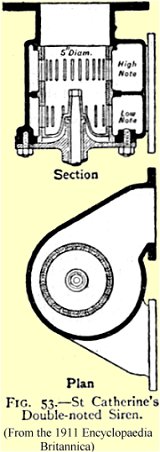

The heart of their siren was a rotating slotted cylinder alternately opening and closing a passageway to either steam or compressed air. Its rotation gave the desired frequency, and it sat in the throat of a long, large horn.

Those sirens were powerful, and most were less isolated than Sandy Hook. In 1900, a newspaper called a Rhode Island siren "the greatest nuisance in the history of the state." Near a Connecticut fog siren, people found that chicks were dying before they hatched.

While people who lived by those large coastal sirens grew nervous, lost weight, and watched as sound curdled their milk, the technology raced on. An amateur organ-builder named Robert Hope-Jones created a tone generator called a diaphone for the Wurlitzer Organ Company. Then he adapted it into the classical low-frequency foghorn sound that we all know from old movies.

That design modified over the years. Meanwhile, World War II required higher-pitched sirens to operate in clear air. We needed them to warn, not of rocks, but of enemy bombers. The Chrysler Corporation built one driven by a 140-horsepower eight-cylinder automobile engine. Same basic sound production, but far more powerful -- almost twice as earsplitting as a jet engine.

The pitch of an air raid siren was near the concert A used by the oboe to tune an orchestra. But there the comparison ends. Come within a hundred feet of one, and ear-protectors give scant protection. The ground shakes, and your vision blurs.

The big, loud sirens still exist. In Hawaii, they warn of Tsunamis. Other big sirens are for other big dangers. And we think of the original Sirens. They did not repel; they attracted. Circe warned Odysseus about the legendary Sirens:

You will come to the Sirens, enchanters of all mankind. They sit in their meadow, but the beach before it is piled with boneheaps of men now rotted away ...

None of that enchantment in today's sirens. They mean danger, just as surely as they did for Odysseus. But there is no longer any come-hither message in the few of those great, wailing sirens that still remain to be heard.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Lamm, M. Feel the Noise: The Art and Science of Making Sound Alarming. Invention and Technology, Winter 2003, pp. 22-27.

For more on lighthouses, see Episode 1523.