The Thames Tunnel

Today, the Thames Tunnel. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1799 the great French engineer Marc Brunel moved to England. He was as grandiose a developer as he was an engineer. His various money-making schemes collapsed in 1821, and he was sent off to debtors' prison. But the Duke of Wellington got him out. England needed his services.

Brunel bounced back, immediately getting into a huge variety of projects. In 1824, he formed a company to undertake the grandest project of them all -- a horse-carriage tunnel under the Thames River. That may not sound like much today; but tunneling under a large river was a truly radical notion two centuries ago.

The next year, Marc Brunel put his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel in charge of operations. (Kingdom was the maiden name of Marc's wife). Isambard was a nineteen-year-old mechanical prodigy who worked like a demon -- both at the tunneling and at publicizing it.

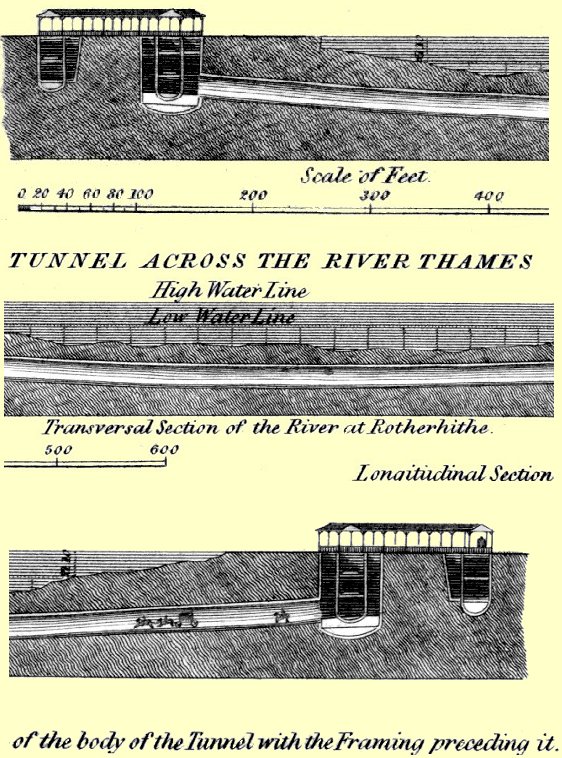

Father Marc invented the first tunneling shield -- an iron structure with thirty-six one-man chambers in it. This shield was driven into the earth as workers dug their way forward, and others followed, building the masonry supports for the tunnel.

By the time Isambard reached his 21st birthday, three hundred feet of tunnel were finished, and he threw himself a great birthday party under the river. By then seven hundred visitors a day paid a small fee to walk in the tunnel as the work went on. All the while, leakage was increasing. Marc furrowed his brow and said, "May [disaster not occur] when the arch is full of visitors." Finally water leakage killed one worker, and it halted the work.

Repairs were made, and the public-relations blitz continued. Marc Brunel held a concert in the tunnel that November, taking pains to praise the acoustics. The clarinet sounded especially nice. He also staged a banquet in the tunnel for fifty notables and 120 miners. This time, Coldstream Guards provided the music.

Then, the next April, water burst in. Six people died, and Isambard was badly hurt. That ended the digging for seven years, but it didn't kill the project. Isambard went down in the diving-bell used to repair the breach. And he boated visitors through the flooded tunnel -- his River Styx. On one of those trips, he nearly drowned Napoleon Bonaparte's nephew Charles, who couldn't swim.

The tunnel was finally drained, and it was finished in 1843. Queen Victoria walked through it, and then she knighted Mark Brunel. But it never did open to horse traffic. Instead, it became a somewhat dubious pedestrian crossing.

Only in 1860, long after Marc was gone, and the year after Isambard had also died of exhaustion at the age of 53 -- only then did rail interests buy the tunnel and make it a part of the London underground. And so it remains today. Isambard did much more. He became the prototypical Victorian engineer -- a heroic artist in iron. But if the ghosts of father and son live anywhere, it can only be here -- down below the turbid waters of the Thames River.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

J. Pudney, Brunel and His World. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd., 1974.

For more on the Brunels see Episodes 1405, 1473, 1402, and 229.

Left, middle, and right sections of the originally planned Thames Tunnel

(From the 1832 Edinburgh Encyclopaedia)