Matzeliger in1924

Today, Jan Matzeliger in 1924. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

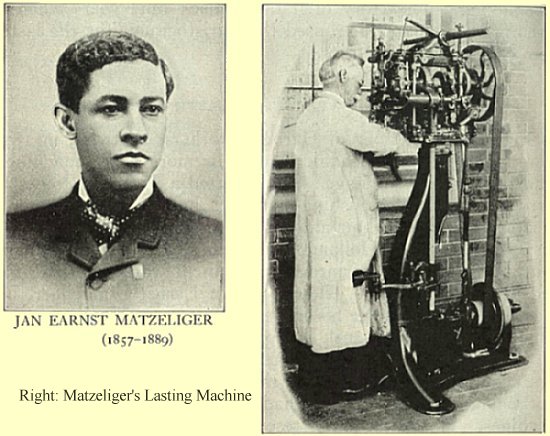

Jan Matzeliger, the black inventor of the automatic shoe-lasting machine, was rediscovered during the 1980s. In 1991 he was even honored on a U.S. postage stamp. For a century after his death in 1889, however, he'd been all but forgotten. So I was surprised last week to find an entire section on Matzeliger in a 1924 book on American inventions.

The '20s were a bad time in American race relations. Opportunities for our black citizens had been closing down since the Civil War. The Ku Klux Klan functioned openly, lynching was common, Jim Crow ever-present. Matzeliger, born in Dutch Guyana in 1852, was the son of a Dutch engineer and a black mother. This old book says that he had a brown complexion, crinkly hair, and a native mother.

As a boy, he apprenticed in a machine shop, and at 19 he set off for America as a merchant seaman. He found work in the Harney Brothers' shoe factory in Lynn, Massachusetts, as a shoe-stitching-machine operator. It was a tough life. He was isolated not only by his race, but by his native Dutch tongue as well. He lodged above the West Lynn Mission, and he joined the Congregational Church, the only church to welcome him despite his race. Quiet and fiercely intelligent, he lived a lonely life, reading and studying.

As a boy, he apprenticed in a machine shop, and at 19 he set off for America as a merchant seaman. He found work in the Harney Brothers' shoe factory in Lynn, Massachusetts, as a shoe-stitching-machine operator. It was a tough life. He was isolated not only by his race, but by his native Dutch tongue as well. He lodged above the West Lynn Mission, and he joined the Congregational Church, the only church to welcome him despite his race. Quiet and fiercely intelligent, he lived a lonely life, reading and studying.

He also thought about the hardest step in making a shoe: First you sew up the top of the shoe; next you shape it over a wooden model of a human foot called a last; then you sew it to the inner sole. It took great skill to bend, shape, and hold the leather top while you stitched it to the bottom. Shoe manufacturers had spent huge sums trying to mechanize that step, and they'd failed.

Matzeliger knew he could solve the problem. He began creating a working model, scrounging parts and going without food so he could pay for materials, all on top of ten-hour workdays! It took years, but in 1882 he filed a patent -- a huge, complex, 15-page document. Naturally, he earned the wrath of the shoe lasters, who saw themselves as the aristocrats of the shoemaking industries.

Lynn businessmen funded a prototype in exchange for two thirds of any profits. By 1885, Matzeliger had a production model ready, but he'd also contracted tuberculosis. He sold out for $15,000. The machine went on to cut the cost of shoes by fifty percent.

He died four years later, but in those last years he found friends in his church. He taught Sunday school, he taught oil painting, and he kept inventing. He left his money to the church that'd seen through the color of his skin. His will also bequeathed those small possessions that'd been central to his life: his drawing instruments, his Bible, and his technical books.

In 1985, the city of Lynn named a bridge on Fayette Street after good and quiet Jan Matzeliger -- small enough recompense for the person who'd done something so fundamentally essential as putting affordable shoes on America's feet.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

A Popular History of American Invention, (Waldemar Kaempffert, ed.) New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1924. pp. 429-433.

Karwatka, D., Against All Odds. American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Vol. 6, No. 3, Winter 1991, pp. 50-55.

I am grateful to Diane Shephard of the Lynn Museum, Lynn, Massachusetts, for her very helpful counsel and for additional images.

This is a greatly reworked version of Episode 522.

From A Popular History of American Invention, 1924