Jan Matzeliger

Today, a black immigrant provides shoes for America. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Jan Matzeliger lived less than 37 years. Most of them were lonely ones. He was born in Dutch Guiana in 1852. His father was a white engineer -- his mother, a black slave. As a boy, he apprenticed in a machine shop.

Quiet and fiercely intelligent, Matzeliger put to sea in a merchant ship when he was 19. His travels took him at last to Lynn, Massachusetts. There he worked as a shoe-stitching-machine operator.

He had tough going. Not only was he black, but his native tongue was Dutch. The Catholic, Unitarian, and Episcopal churches gave him a cold shoulder. So he took up residence inside his own head. He read and studied. He also thought about the most difficult step in making shoes.

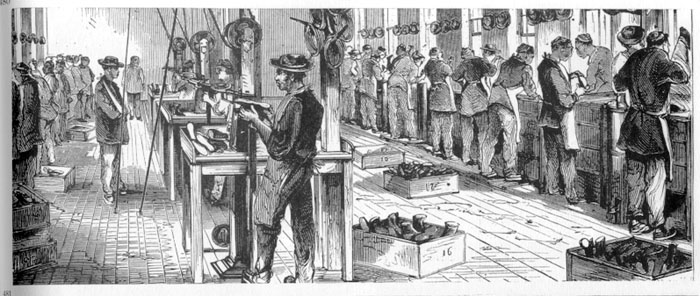

First you sewed the shoe top together. Next you shaped the top over a wooden model of a human foot, called a last. Then you sewed the top to the inner sole. It took great skill to bend, shape, and hold the leather top while you stitched it to the bottom. The shoe machine people had invested huge sums in trying to mechanize that step. They'd failed.

Matzeliger knew he could solve the problem. He began creating a working model. He scrounged parts and went without food so he could pay for materials. All this on top of ten-hour work days! It took five years, but by 1882 he'd filed a patent. It was a huge, complex, 15-page document.

Two businessmen funded the prototype in exchange for two thirds of any profits. By 1885, Matzeliger had a production model ready. At that point, he sold out for $15,000. He went on to new inventions while others got rich on his genius.

Matzeliger's last five years were happy ones. He'd gained membership in the North Congregational Church. He'd gained friends. He taught Sunday school, and he taught oil painting. He also poured out his inventive genius on new machines. Meanwhile he'd cut the cost of making shoes in two.

When tuberculosis claimed him, his will left a big piece of his fortunes to the Church that'd seen beyond the color of his skin. He made special provisions for his drawing instruments, his Bible, and his technical books -- the things that'd really mattered to him.

In 1984, Lynn, Massachusetts, finally named a bridge after this good and quiet man who'd done so much for the city -- who'd done so much for all America. Finally they honored this triumph of the mind -- against all odds.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Karwatka, D., Against All Odds. American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Vol. 6, No. 3, Winter 1991, pp. 50-55.

Jan Matzeliger, finally memorialized on a postage stamp

Shoe lasting in a shoe factory before the Matzeliger

mechanized the process (clipart, source unknown)