Creative Collaboration

Today, an art exhibit explains collaboration. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Charles Schultz delighted us all for years with his Charlie Brown comic strip. In a TV interview, not long before he died, Schultz said, "I never accept suggestions from people." Coming from that delightfully humble man, the remark was a jolt. But turn it about in your mind, and it begins to make sense.

The Charlie Brown strip was so successful just because it was intensely personal. The tension and flow of themes among Charlie, Lucy, Snoopy, and the rest were the flux of Schultz's own meditations. An outsider could just as well have assisted Schultz by telling him to be taller or to grow red hair.

A new art exhibit now helps me to understand what I might call "The Charlie Brown Collaboration Problem." The title of the exhibit catalog is Jane Hammond, The John Ashbery Collaboration: 1993-2001. When Pulitzer-prize-winning poet John Ashbery explains the meaning of the word "collaboration" here, you might think he's mocking it. He tells how artist Jane Hammond asked him, simply, for a list of titles of possible pictures. Ashbery says,

In about four minutes I had made a tour of a walled-off room somewhere in my subconscious and returned with a clutch of "titles" which were actually labels of curios in my own musée imaginaire.

Ashbery uses the expression musée imaginaire for his museum of the imagination -- for the jumble of ideas we turn to whenever we set out to create anything. The musée imaginaire serves artist, poet, and cartoonist alike.

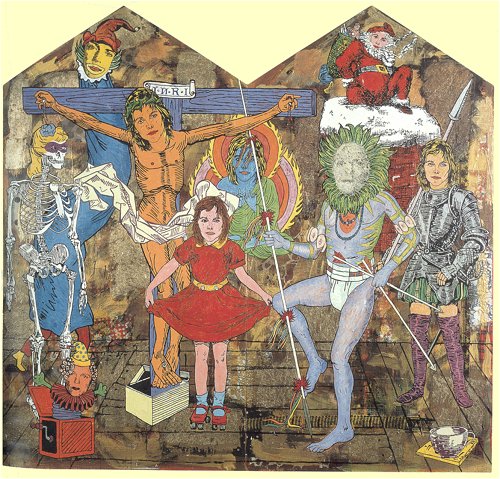

Hammond forms surreal collages to match Ashbery's titles. For the title Wonderful You, she forms an unsettling diptych with a fairly attractive woman's face appearing on a little girl, a savage dancer, Joan of Arc, Jesus, Santa Claus, and a skeleton. It is a fine commentary on romantic love as an infection of the mind.

Another title is Surrounded by Buddies. This time a man stares into a mechanical box, which generates cubes. Each cube contains a salacious scene of his own devising. And we're back to collaboration. The artist and the poet say watch out for the warmth of easy friendship, for we use it to deceive ourselves. Collaboration has to be sterner stuff than being "surrounded by buddies."

More titles: Long-Haired Avatar, Irregular Plural, Midwife to Gargoyles. Fill in your own images and you, too, become part of their collaboration. For you and I do touch one another -- just never quite the way we mean to. No one said to Schultz, "How about a dog who thinks he's fighting the Red Baron?" But Schultz listened to his world. Hammond took that one step further and said to Ashbery, "You write titles; I'll let them work on my subconscious."

Collaboration lies behind any creative work. It's simply that process in which you and I learn to listen to each other. We allow one another to open the door to that vast musée imaginaire that we all possess -- and struggle to utilize fully.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Jane Hammond, The John Ashbery Collaboration, 1993-2001. Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art, 2001. I am grateful to Kim Howard of the Blaffer Gallery for providing this source.

You may see these pictures at the "Jane Hammond, The John Ashbery Collaboration, 1993-2002" exhibit at the Blaffer Gallery, the art museum of the University of Houston, September 28 through November 24, 2002.

Wonderful You #2, by Jane Hammond (from the collection of the artist)