Cap Wigington

Today, a remarkable architect. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

St. Paul, Minnesota, gave mixed messages to a child of the 1930s. The schools were integrated, and classes preached racial equality. But then we black and white kids went off to our respective neighborhoods. Brotherhood ended when school let out.

That's how it went in my Webster Grade School and in Marshall High School. Now a remarkable book casts new light on all that. It is Cap Wigington: An Architectural Legacy in Ice and Stone.

Cap Wigington was a very important architect. He designed both my schools. And he was black. Indeed, his office was located right in the area where my black schoolmates went home each night. And we had no idea who'd designed our schools.

Wigington was born in 1883 in Lawrence, Kansas. His family moved repeatedly, and he had to struggle to get schooling. He finally finished high school in Omaha and, owing to a remarkable artistic talent, found work as an apprentice to an Omaha architect.

By the age of 31, he'd designed homes and churches in Omaha. Then he moved to St. Paul, where he felt prospects might be better.

And they were. As the result of a competitive exam, he became America's first black municipal architect. Soon after, he got his name, "Cap." His given name was Clarence, but just after America entered WW-I, Wigington petitioned the Governor of Minnesota to form a black battalion of the Minnesota Home Guard.

The governor saw that this was a way to promote racial equity without paying a huge political price. He granted the request. As captain of the new battalion, Clarence soon became "Cap."

So Wigington kept designing my city. It's all there: The lovely Highland Park Water tower we used to visit. The warming house at St. Clair Park where I'd collect myself between toboggan runs. The first air terminal I ever entered. The Como Park Zoo. He created the clean collegiate-Gothic designs of those schools that were trying to show us what racial equity might look like.

But that was the stuff of everyday life. Another St. Paul landmark lay in off in a special dream world. Each winter, cold St. Paul puts on a huge Winter Carnival. And a weather-dependent part of that fair is building a great life-size Ice Palace.

Wigington designed those colossal Camelots during my school years. Strange and otherworldly, they lasted only until the spring thaw. Yet, long after Wigington's creation of a real world is forgotten, we'll still see those grand crystalline fairylands.

Cap Wigington himself lived in an unreal world -- one stained by racism, yet completely accepting of his genius. As an old man, he wrote this:

Each night ... I thanked Almighty God for granting me some degree of ability [and a] liberal appreciation of my good neighbors ... .

Well, a good neighbor he was. He built my town. He created the texture of my childhood.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Taylor, D. V., Cap Wigington: An Architectural Legacy in Ice and Stone (with Paul Clifford Larson). St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001.

I am grateful to Margaret Culbertson, UH Art and Architecture Library, for suggesting the topic and providing the Taylor book.

For more on Wigington, and his many designs, Click Here.

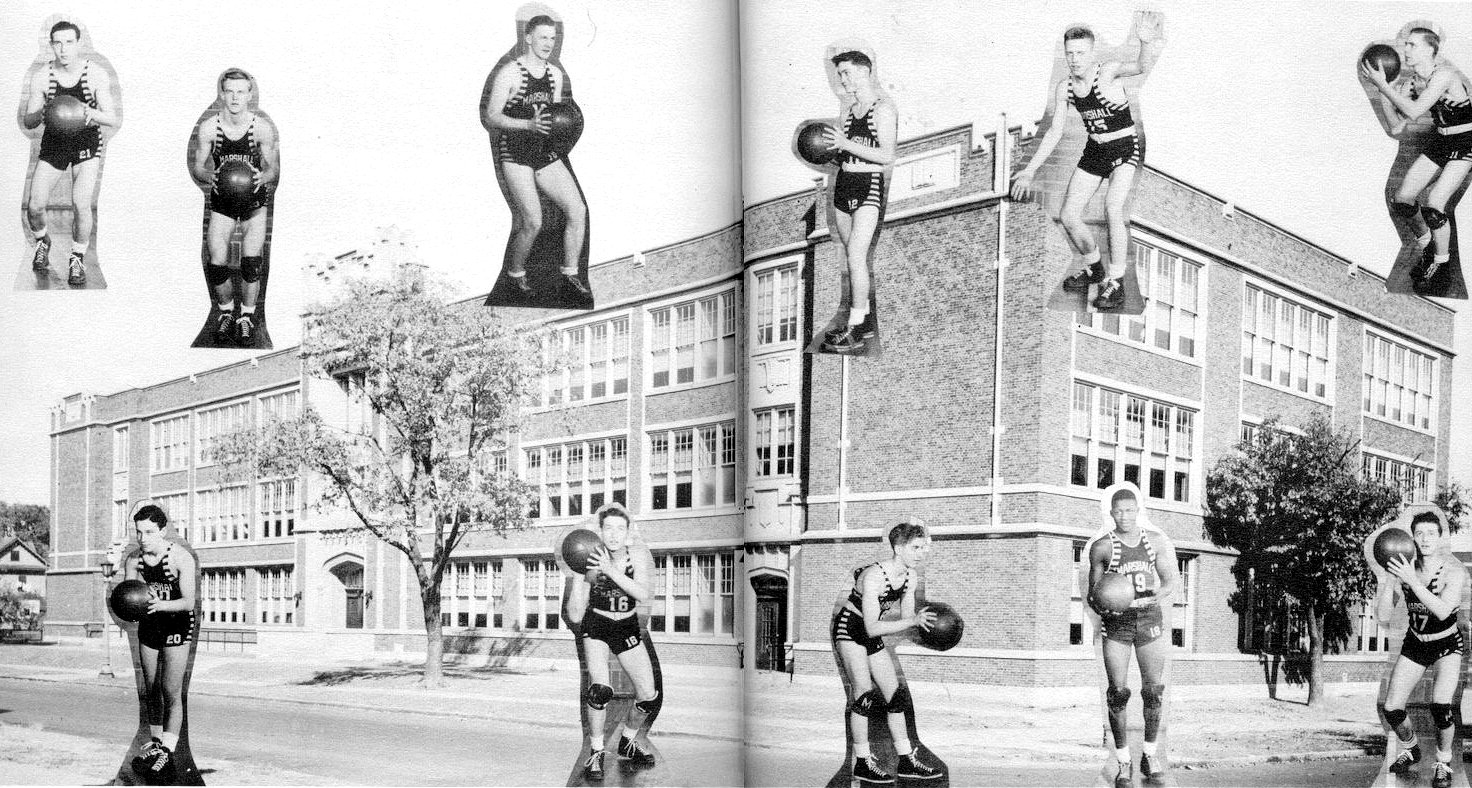

John Marshall Senior High School, designed by Cap Wigington in 1924. (The image above is from the 1944 school annual, The Magistrate. Notice one Black player on the basketball team. He is classmate Percy Zachary, who went on to play football for the University of Minnesota. He was named to the 1952 All Big Ten First Team.)