Lordy Byron and Steam

Today, a strange connection between Lord Byron and steam power. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

John Byron, father of poet Lord Byron, was as colorful as his son. People called him "Mad Jack" behind his back. He was a notorious wastrel. After Mad Jack Byron burned up his fortune, his first wife fled. He married his second wife, wealthy young Catherine Gordon, in 1785. They lived on the Byron estate near Nottingham. He was just finishing off her fortune three years later, when his poet son was born. Catherine finally took their son off to Scotland. Mad Jack died when the boy was only three.

John Byron, father of poet Lord Byron, was as colorful as his son. People called him "Mad Jack" behind his back. He was a notorious wastrel. After Mad Jack Byron burned up his fortune, his first wife fled. He married his second wife, wealthy young Catherine Gordon, in 1785. They lived on the Byron estate near Nottingham. He was just finishing off her fortune three years later, when his poet son was born. Catherine finally took their son off to Scotland. Mad Jack died when the boy was only three.

Around the time of his second marriage, Mad Jack became fascinated with staging naval battles in an artificial pond on his estate beside the Neer River. Downstream, the Robinson family had set up a mill. The land was fairly flat in that region, and they'd built a reservoir to supply their delicate system of waterwheels.

The autocratic Mad Jack began diverting the river water for his pond. The Robinsons filed a lawsuit, but without much hope. Historian Richard Hills tells how, in desperation, they finally wrote James Watt in August, 1785, and ordered a ten-horsepower steam engine to replace their water wheels. They said,

[We] beg you will give due attention to our situation,

and lett Lord Byron see that we can do without him.

Watt had received the last of his last major steam engine patents only the year before. The Robinsons were gambling on a truly cutting-edge solution to their problem. By the following February, the engine had been built, shipped, and installed.

Before the engine was in place, Mad Jack Byron lost the lawsuit. The need for the engine was no longer urgent. On top of that, its installation had been faulty. The Robinsons continued their conversion to steam power, but now they moved more cautiously. First they installed one of the older engines that'd been in use before Watt. Then they ordered a second Watt machine.

The Robinson's conversion to steam was a troubled process -- a lot like using software in its beta-test phase. For years, the Robinson family sparred with Watt over how much post-installation service was due them. Meanwhile, in the company backrooms, Watt and his people worked feverishly to improve subsequent engines.

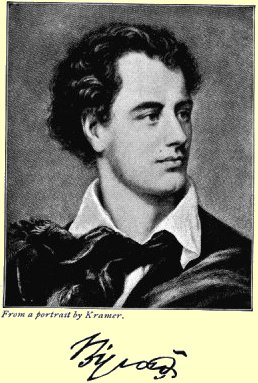

Watt died in 1819, while the younger Lord Byron (the poet) was traveling in Italy. Watt had systematically improved his engines and become the most famous engineer in the world. Byron, who would die young five years later, was the rock star of English poetry.

Their lives touched only tangentially when Byron's prodigal father drove a miller to become one of the first users of Watt's new engines. At the same time, he drove his wife off to Scotland where his son found the raw material that would shape a poetic vision. In his poem Don Juan, Byron writes,

I 'scotched, not kill'd, the Scotchman in my blood,

And love the land of 'mountain and flood'.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Hills, R. L., Power from Steam: A History of the Stationary Steam Engines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Chapter 5. My thanks to Lewis Wheeler, UH Mechanical engineering Department, for providing this source.

I am grateful to James Pipkin, UH English Department, for additional counsel.