An Old Machinist's Handbook

Today, a revolutionary's handbook. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Watt's new improved steam engines had been around for forty years in 1825. That year, John Nicholson published a work called The Operative Mechanic and British Machinist. Today such handbooks are collections of hard information about thread sizes, standard metal thicknesses, and working tolerances. They deal in the specifics of technology and say very little about its broad sweep.

But Nicholson's handbook came out of the smoke of the Industrial Revolution. A dazzling profusion of new high technology had come into being, and this eight-hundred-page, two-volume compendium sets out to explain it all. This is no shop guide to nut and bolt selection. The mechanics and machinists he's talking to are the engineering designers of the early nineteenth century.

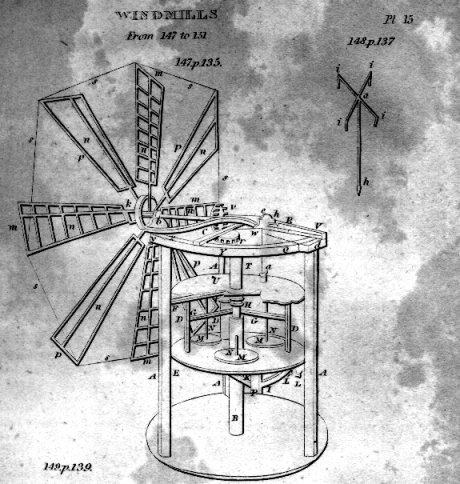

I thumb through the beautiful plates looking at power transmission devices, systematic studies of animal and human power output, hardware for harnessing and controlling water wheels, windmill systems, flour mills, steam engines, paper-making, printing, weaving, pumping, and so on and on.

The book says little about how to make these devices. It's meant for people who already know the machine tools and processes behind this glorious inventory of machines. But my eye is drawn to the inscription in the front. Let me read it for you:

In an age like the present, when the rich ... identify their interests with the welfare of the poor, ... when the wise ... [further] sound principles and useful knowledge among ... the most important, though hitherto ... most neglected, portion of the community, [no one] can view the future [without anticipating] change as brilliant in its effects, as it is honorable to those ... engaged in promoting it.

Nicholson expresses two basic sentiments of the Industrial Revolution in this passage. One is that technologists are responsible for improving the lot of the poor. The other is that good work rewards the technologist who does it.

Those of us raised on Charles Dickens have trouble believing that such high principle drove the people behind the Industrial Revolution. But Dickens was still in grade school in 1825. By then, the engines of greed were beginning to tear the fabric of what'd been idealism. People sitting in offices, away from the noise and smoke, were creating the workers' hell that Dickens would begin describing fifteen years later.

What we see here is the last of a breed that really did, in Nicholson's words, identify their interests with the welfare of the poor. The Industrial Revolution was one arm of late eighteenth-century social revolution. It eventually did produce nineteenth-century smoke and factories, but it was fueled first by idealism.

And, as we look at Nicholson's woodcuts, idealism is what we still see. We see the beauty, grace and hope that created all this machinery in the first place.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Nicholson, J., The Operative Mechanic and British Machinist; Being a practical Display of the Manufactories and Mechanical Arts of the United Kingdom. London: 1825 (2nd American Edition, Philadelphia: James Kay, Jun. & Co. Printers, 1831). My thanks to colleague Larry Witte for this source. This edition is now in Special Collections, UH Libraries.

I first did a version of this episode in 1988 as Episode 200. Then I did this revised version in 2002. In 2010, Patrick Hoyt pointed out that Nicholson's handbook had been made available on line. Here is the 1825 London. While it's the original, it lacks any illustration.

Nicholson's preface

Nicholson's instruction on building a windmill

Images above, courtesy of Larry Witte, from The Operative Mechanic and British Machinist, 1831