Marie Lavoisier

Today, meet Marie Lavoisier. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

When scientist Antoine Lavoisier was beheaded during the French Revolution, he left behind a widow whom history remembers as his beloved and supportive wife. Now, as historian Roald Hoffmann looks more closely at Madame Lavoisier, he finds much more than the shadow of a great man.

Born Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze in 1758, she married the 28-year-old lawyer/scientist Antoine Lavoisier when she was only thirteen. They'd been married 23 years when the Revolution hauled him in on charges of having collected taxes for the crown.

Born Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze in 1758, she married the 28-year-old lawyer/scientist Antoine Lavoisier when she was only thirteen. They'd been married 23 years when the Revolution hauled him in on charges of having collected taxes for the crown.

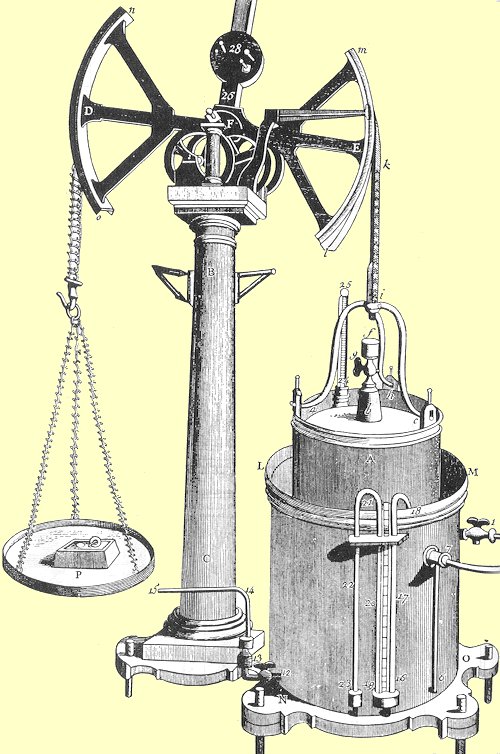

Marie had spent her teen years studying chemistry and learning to read English. She also learned art from the revolutionary painter David. As Hoffmann traces old records, he finds Marie managing the schedule of her husband's laboratory and creating fine detailed drawings of apparatus. She receives no credit, but the figures in his books carry her signature. Her drawing of an experiment on respiration shows Antoine directing the work while she records data at a table off to the side.

And so we wonder: Was she the perfect secretary or a scientific collaborator? When Irish scientist Richard Kirwan published An Essay on Phlogiston, Marie Lavoisier translated it into French. Her husband then wrote rebuttals for each section. Her role was anonymous in the first French edition of Kirwan's monograph. But the later editions all name her as the translator.

And so we try to see the dynamics of interaction between the husband and wife. Lavoisier's chemistry was new turf. Recent improvements in instrumentation had sent science off in new directions. Both Lavoisiers were learning from the ground up.

After her husband's death, Marie ran a scientific salon. The statesman Pierre-Samuel duPont de Nemours, friend of Thomas Jefferson and namesake of the Dupont Company, courted her until she rejected him. In 1805 she married the notorious expatriate American scientist, Count Rumford. That union quickly devolved into raging squabbles and lasted only a few months. She lived on to the age of seventy-eight, and Hoffmann laments that no one has written her biography. He thinks there should be an opera.

Anyone familiar with Lavoisier knows David's famous painting of the couple. Antoine sits writing, while Marie bodies up against his shoulder. He turns to look at her, more than just distracted. Her hand hovers next to his writing hand as she gazes out at us with a faint smile. David knew this couple well.

He painted them a scant two years after Mozart made his own revolutionary statement in the opera The Marriage of Figaro. Mozart has the servant Figaro singing, "You may go dancing, but I'll play the tune." Perhaps David was the librettist for Marie's opera, but his version is less harsh. I like to think that his Marie, unlike Figaro, knows that history will have the last word.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Hoffmann, R., Mme Lavoisier. American Scientist, Vol. 90, Jan-Feb, 2002, pp. 22-24.

The complete text (in English) of Lavoisier's Traité Elémentaire de Chimie (1789), illustrated by Mme Lavoisier, may be found in: Lavoisier, Fourier, Faraday, (Great Books of the Western World series.) (Robert Maynard Hutchins, and Mortimer J. Adler, eds.) Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952. See Lavoisier, A. L., pp. 1-160.

See the David painting of the Lavoisiers, and learn more about it here.

Below: from Traité Elémentaire de Chimie, Marie Lavoisier's drawing a gazometer: