The Aging of Books

Today, we watch books grow old. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

One day, after I'd been studying some hundred-year-old books in the University Library, I glanced at my sleeve. It looked like it'd been rubbed on rusty pipes. Every time my arm had brushed the stack of books, some of the old binding had flaked off on my shirt.

It turns out that that was just the tip of an iceberg. Books made in the last two hundred years are especially cursed with short lifetimes. Their pages become brittle and brown; their bindings crack; they eventually fall apart.

Some of you may have had a chance to see a five-century-old Gutenberg Bible -- one of the first printed books. If you have, you were surely struck by the fine condition of its pliable, snowy-white pages. It is a startling fact that surviving fifteenth-century books are usually in better shape than the ones your great-grandparents read.

We see why when we look at ancient paper. Papyrus, from which we take the word paper, was a wonderful material, made from reed fibers. But it wasn't available in northern Europe. Medieval scribes had to use parchment -- the skin of calves or sheep. Parchment was a very durable writing material. An old handwritten parchment book often looks as good as new.

But it took the far cheaper linen-based paper to supply the voracious new printing presses. Gutenberg printed some of his Bibles on parchment, but most were less expensive ones, printed on linen paper.

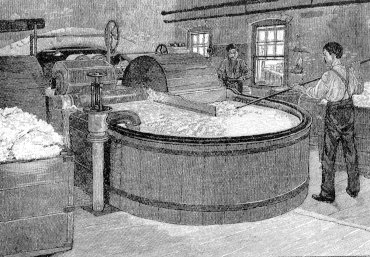

That paper is made by reducing linen rags to a fiber slurry. When the slurry is drained over a fine mesh, the fibers reform themselves into a sheet of superb paper. While real linen paper is a lot cheaper than parchment, it's still very costly by today's standards. And those paper Bibles were wonderful books, and they've stood up remarkably well.

The demand for printed books skyrocketed after Gutenberg. And the cost of paper had to be cut. In the seventeenth century, alum was used to speed the reduction of fibers to a pulp. But heat and humidity cause alum to react into hydrochloric acid. Then later paper-makers used sulfuric acid or chlorine to bleach colored rags.

And when people turned to wood fibers in the early 19th century, still more vicious chemicals had to be added to digest the fibers. The first widely-used wood-based papers have fared very badly. Lay a piece of that paper over your palm and close your fist. You'll find yourself with a handful of paper chips.

Graduate students sometimes wonder why they're asked to buy expensive rag paper for their theses. Yet old theses are often among the best preserved books in a library. Library books from a century ago are almost all being eaten away from within by acids and other chemicals.

It's all a big trade-off, of course. Our civilization wouldn't be where it is if we hadn't found ways to make cheap books available. But it's really frightening to have to watch our heritage crumbling away under our fingers. I really hesitated to brush off my sleeve that day as I left the library.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Dean, J.F., The Self Destructing Book. Yearbook of Science and the Future. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 1989, pp. 212-225.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 216.

For more on Gutenberg, see Episodes 628, 753, 756, 894, and 992.

Typical 19th century paper pulping process