Looking for the Engineers

Today, where did all the engineers go? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

A colleague asked a group of freshman engineering students to write down nine names: three famous scientists, three famous inventors, and three famous engineers. Few had any trouble with scientists. Most could name one or two inventors. But few of the engineering students could name any famous engineers.

What are the implications of that? There are plenty of names: Vitruvius, Watt, Brunel, Eiffel, Mulholland, Rickover, Herbert Hoover, Jimmy Carter, Nevil Shute, Henry David Thoreau, and Josiah Willard Gibbs. But we call Vitruvius and Eiffel architects. We call Watt and Brunel inventors, and Gibbs a scientist. We call Hoover and Carter political figures, and Rickover an admiral. We know Nevil Shute and Henry David Thoreau only as writers, even though both did major engineering work. Did you know that cellist Carlos Prieto and sculptor Alexander Calder were both engineers?

I used to be more confident in defining engineering than I am today. The word engineer has evolved from the word engine and from the word ingenuity. Some people focus on engineering as a profession -- an enterprise in which the public places its trust. Others see it as a source of new technology. Some expect engineers to expand our knowledge of means for building things.

An essential tension lies among these different pursuits. The most sober and reliable professional has little interest in potentially dangerous new ideas. At the same time, codes and standards are pretty far off the radar screen of someone deeply involved with, say, creating a new turbine-blade cooling system.

Maybe we need to look inside schools that teach engineers. There we find a three-part curriculum. Math and science is one part; technical engineering is another; liberal arts and writing form the third. Engineers get one of the best liberal educations available. In fact, some schools give their engineers a Bachelor of Arts degree instead of a Bachelor of Science.

That term liberal education refers to the tradition of educating students to become effective free citizens -- people capable of making and carrying out good choices and decisions. (It has nothing to do with politics.) It refers only to equipping a person with freedom of choice. It's about creating effective citizens.

People who see the world with an engineer's eye are typically able to move in many directions. Some become scientists, others builders, managers, presidents or beach bums, writers or artists.

Naturally, since engineers are so seldom just one thing, our students have trouble identifying famous ones. They often don't know them as engineers. They don't yet see that they're also being educated, not to do just this or that, but to maximize their own potential. Watch those students twenty years from now. Watch them. Like their predecessors, they'll form their world. But, like their predecessors, they too will do so under many guises.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

I am grateful to my colleague Keith Hollingsworth, University of Houston Mechanical Engineering Department, for sharing with me his conversation in that freshman classroom.

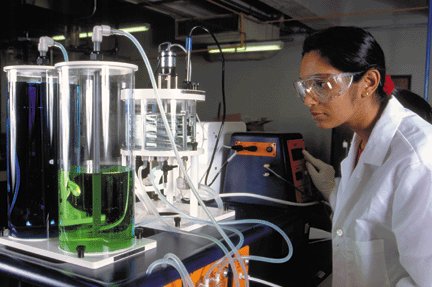

Student in the UH undergraduate Chemical Engineering Laboratory