Of Nature and Multiplication

Today, nature and multiplication. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Something struck me yesterday in the large sub-basement that once housed much of our University Law Library before the flood of 2001. I paced the area, and did the multiplications. The flood, it turns out, had filled it with almost 20,000,000 pounds of water.

That number seemed almost unimaginably large. We look at it and think there must be some mistake. Nature constantly catches us by surprise in the way it generates huge numbers. I first saw that basement as a mere fifty-two paces across. The capacity of a three-dimensional volume sneaks up on us here, as in any situation.

Since volume is the product of three numbers it comes out larger than we expect. Anyone who first enters the Space Shuttle mid-deck is struck by how small it is. But it works because astronauts live in all three dimensions of that space, not just on its floor.

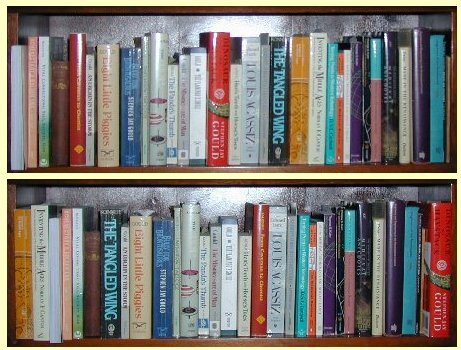

It is through such multiplications that nature generates vast numbers in small spaces. The bookshelf in front of me holds sixteen books. Are they in the best order? How many ways might I rearrange them? The answer is sixteen factorial -- sixteen times fifteen times fourteen, and so on down to one.

It comes to over twenty trillion arrangements. The shelf next to it, with thirty-two books, now offers roughly ten to the power thirty-five possible arrangements. And that's only a few books on one shelf. In our universe, made up as it is of atomic arrangements, the number of things that can happen is infinite by any conception of that word.

And we aren't done yet. For, by now, we all know about the butterfly effect. We know that tiny influences utterly alter large outcomes. And a butterfly is, in fact, a Sherman tank of an influence compared with the flutterings that truly influence outcomes. Random molecular movements create infinite rearrangements, any one of which is enough to redirect human history.

The complexity of it all reminds me of a story I once heard about Albert Einstein. He supposedly used the same soap for washing and for shaving because to use two soaps would add needless complication to his life. Einstein was on to something there.

Nature surrounds us with her multiplications. The terrible tyranny of large numbers wells out of every cranny of our lives -- our basements and our bookshelves. Even now, as I try to think of ways to dodge that tyranny, I write with the help of a computer that's doing nearly a billion operations per second.

It really does depend on how we hold things up to the light. The Space Shuttle, which first seems far too small to accommodate six people, becomes large enough just because of those multiplications. The fact is that there's more space there than we would've dreamt, just as there's more opportunity here on Earth than any of us can ever imagine. And that's where hope is ubiquitous. It can be found even in that devastated basement library.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Two out of roughly 263,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 ways in which I have, over the years, arranged the thirty-two books on this particular bookshelf