Power in Colorado

Today, we install a dynamo on a mountaintop. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

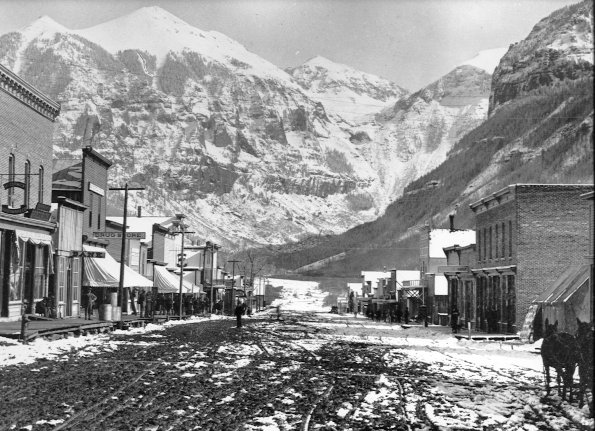

By 1900, the legendary West was almost gone. It was vanishing so rapidly that we have to look closely to see where it left us. Take the case of Telluride, Colorado, formed in 1878 and named after the tellurium that's to be found in certain gold ores.

By 1888, the California Gold Rush was over and Telluride's miners had settled into the laborious work of tunnel-mining and milling low-grade ore. For power, they used small steam engines. First they burned the local wood. Then they used burros to cart in coal. Coal was costing an outrageous forty dollars per ton.

The "Gold King" Company was nearly bankrupt when someone pointed out what was going on in the East. Six years earlier, Edison had created the first public electric power system to provide direct current for his new electric lights. Soon after, George Westinghouse had followed suit with an alternating-current system.

The Gold King people wasted no time. In three years, they'd built a Westinghouse-style hydroelectric power system. A six-foot Pelton water-turbine, off in the mountains, drove two, one-hundred-horsepower dynamos. Three-thousand-volt power traveled two and a half miles in bare copper wire to an electric motor at the mine.

Hair raising stories are told about workers breaking six-foot electric arcs around the motor by waving their hats through them. They installed the system amid blizzards, avalanches, minus-forty-degree cold snaps, and huge water-flow variations -- all far from any technical support. They opened a school to train rough-hewn electrical engineers who could manage the system.

It took a scant twenty years for those two little dynamos to expand into the Telluride Power Company. By the early 1900s, it was supplying forty thousand horsepower to three states.

If you have the chance to ski at Telluride, or to ride the Durango-Silverton narrow-gauge railway to the top of the next mountain range, try shutting out the amenities -- the highways, elec-tricity, cold-weather gear, and hotels. Add death and disease to that. Who were these people who went into the Rockies to dig gold? It took people who lacked the most rudimentary caution to do that -- and to instantly absorb new technology at the same time.

Only nineteen years later, in 1910, the government began a vast hydroelectric project. It was a dam across the Mississippi at Keokuk, Iowa. My father, earning money for college that summer, worked as a laborer on its cofferdam. The Telluride power plant had been the work of nineteenth-century pioneers. Now the Keokuk Dam would harness the Mississippi River and enter into the stories that made up my own childhood.

When did the Wild West turn into Modern America? In the blink of an eye is the answer. Change, too large to comprehend, was complete before we realized it had even taken place.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Lavender, A Rocky Mountain Fantasy: Telluride, Colorado, (Telluride: San Miguel County Historical Society, undated).

Anyone interested in details of turbine selection and the appropriateness of the Pelton Turbine in this setting, will find a complete analysis by clicking on Harold Iverson's Hydraulic Machinery course notes, and checking Section 12.0.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 171.

For a full size image of the view looking east down the the main street of early Telluride, click on the thumbnail above.