Joel Dorman and Ester Steele

Today, we meet two very special teachers. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

J. Dorman Steele was born in 1836 in Lima, New York, the son of a clergyman. He finished college, became a teacher, and was a principal at only twenty-three. He married a music teacher, Esther Baker, daughter of another clergyman, just before the Civil War.

In 1861, Steele raised a regiment and went off to fight in Virginia. He was badly wounded, hovered for weeks between life and death, and then finally returned to another principal's post in New Jersey. From then until J. Dorman died at the age of only fifty, he and Esther worked together. They became major late-nineteenth-century textbook writers. They also had some very sound beliefs about teaching. When he found discipline foundering in one of his schools, J. Dorman wrote,

I [became convinced] that the germinal idea of discipline was self control; and that the true aim of the schoolmaster was not to teach the pupil how to be governed by another, but how to govern himself.

We might well remember that when we're tempted to create discipline by imposing strict controls. It was Steele who created the honor system, and he had fine success with it.

We might well remember that when we're tempted to create discipline by imposing strict controls. It was Steele who created the honor system, and he had fine success with it.

The Steeles also believed that textbooks often became self-indulgently long. They realized that textbooks must also be self-disciplined. In 1867, J. Dorman published the first of his Fourteen Weeks series -- a set of science textbooks, each meant for a fourteen-week course. Most are less than three hundred pages in length.

Esther and J. Dorman Steele also coauthored a Brief Histories textbook series. There again is that fine emphasis on brevity. One biographer thinks that these were the best of the many Steele books.

But what I have are several of J. Dorman's science books, and they're all fascinating. The fourteen-week physiology course seems very old-fashioned since he wrote it just before medicine began making huge advances. His physics book, on the other hand, followed an enormous leap forward in that field, and he was right on top of it.

He accurately articulates the new mechanical theory of heat. He also tells us that radiant energy rides upon the ether, which occupies all empty space. That idea was also new, and it lasted until relativity and quantum theory displaced it.

Fine illustrations draw you in, as does the prose. What comes through is something that marks any great textbook. It is love: love of the subject, love of teaching, love for the students who use the book. Both Steeles were fueled by strong religious imperatives. When J. Dorman died, Esther wrote this on his tombstone:

His true monument stands in the hearts of thousands of American youth, led by him to look through Nature up to Natures's God.

And the last line of his physics book is a piece of advice equally valid as religious conviction or as secular common sense. He says,

To the thoughtful mind, all phenomena have hidden meaning.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Steele, J. D., Fourteen Weeks in Human Physiology. New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1872.

Steele, J. D., Fourteen Weeks in Physics. New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1878.

Steele, J. D., Popular Chemistry. New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1887.

Steele, J. D., and Jenks, J. W. P., Popular Zoology. New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1887. (This book was completed posthumously by Jenks. For more on Jenks, see Episode 1071.)

See also article in the Cyclopaedia of American Biography and other biographical dictionaries.

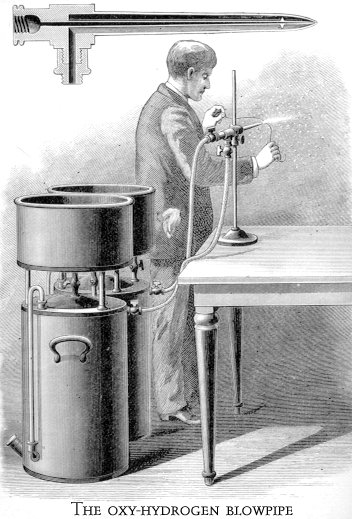

From Steele's Popular Chemistry

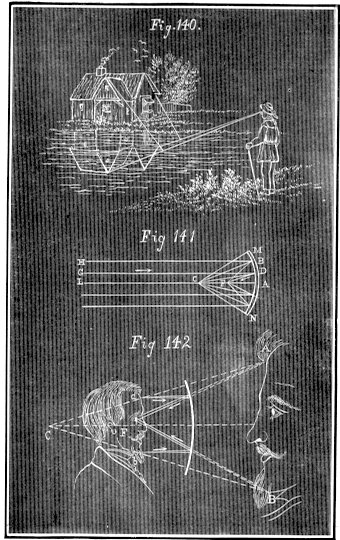

From Fourteen Weeks in Physics

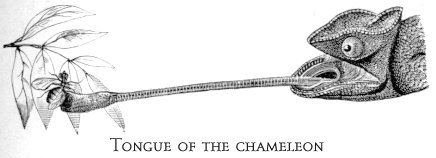

From Steele's Popular Zoology

Steele shows an instructor how to use the blackboard to illustrate the reflection and magnification of images.