Physiology in 1872

Today, let's look at medicine when my grandfather was young. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

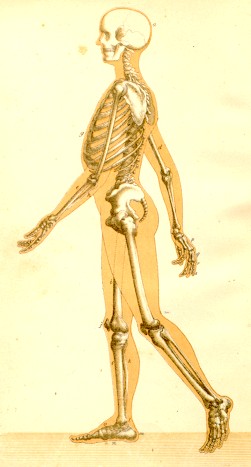

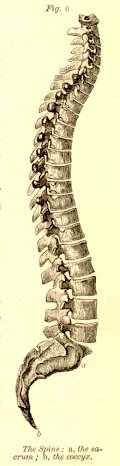

I recently picked up a 14-week course in human physiology for high school students written in 1872. It makes a great window into the recent past. The book's engravings give a sane and balanced picture of our bodies' workings -- a picture that's dated less by what's said than by what's left unsaid, 126 years ago.

It begins with conventional anatomy: the skeleton, muscles, internal organs. It calls the skeleton the "house we live in," and it goes on about the structural beauty of our bones:

The hand in its perfection belongs only to man. Its elegance of outline, delicacy of mould, and beauty of color have made it the study of artists; while its exquisite mobility, and adaptation as a perfect instrument, have led philosophers to attribute man's superiority even more to the hand than to the mind.

The author clearly thinks like a structural engineer. He finished his book at the same time engineers were finishing the Statue of Liberty and the St. Louis Bridge. "The heart is the engine which propels the blood," he says. "The skin is a tough close-fitting garment for the protection of the tender flesh." "Putting food into our bodies is like placing a tense spring within a watch."

A book like this, written today, would lay far greater stress on keeping that watch in good repair. The author's health maintenance methods are okay, but he goes little beyond lifestyle and emergency care. Who'd argue with fresh air, exercise, and clean living? He also sees the dangers of tobacco more clearly than my generation did. But he wrongly calls alcohol a stimulant, and he recommends it as medicine when our "vital energies" are down.

The huge gulf setting this book apart from today is the lack of any germ theory of disease. His section on False Ideas of Disease explains how healers once thought evil spirits caused sickness, while contemporary science has learned that:

... disease is not a thing but a state. When our food is properly assimilated, the waste matter promptly excreted, and all organs work in harmony, we are well. Sickness is discord as health is concord.

But he can offer only cold comfort when that concord breaks down. His cures for illness include purgatives, sweating, compresses, mustard plasters, and beef tea.

This was medicine when my grandfather was young. That recently, our world not only had no antibiotic medicines, it also knew nothing of the germs that antibiotics attack. It was a world where anesthetics were still used only now and then for surgery. A world without X-rays or even domestic fever thermometers. A world where we fought pain with camphor, cloves and sometimes opium. Blood transfusions were known, but they lay out on the far fringe of alternative medicine, in 1872. And life was decades shorter.

Do you harbor any doubts that technology serves the human condition? If you do, pick up one of these old books. Find out just how much better we fare -- than Grandpa did.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Steele, J. D., Fourteen Weeks in Human Physiology. New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1872.

Images from Fourteen Weeks in Human Physiology, 1872