A Theatre of Machines

Today, the first handbooks. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I was still a teenager when I first began to live out of a set of books about my chosen work of engineering. Marks' Mechanical Engineering Handbook, Dwight's Mathematical Tables, and the like. Nowadays, sellers of old books look down upon that literature and let the older versions fall into decay. Yet America, with its lack of skilled craftsmen, was built upon books of this ilk.

The handbook literature traces back to the early fifteenth century. In some sense it even traces to the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Although Leonardo's descriptions of machinery never reached print, they probably influenced a new literary form called the Theatre of New Machines. That title recurred for almost two centuries after Leonardo.

A typical theatre of machines was a book heavily illustrated with block prints. One of the earliest was Jacques Besson's Book of Mathematical and Mechanical Instruments, published in 1571. At first such books said a lot about power generation and transmission. Four centuries ago, the term mathematical instrument might refer to a complex system of pulleys. Later it was applied to astronomical, surveying, and timekeeping instruments.

The old books copied one another. Each new one took up old ideas and added new ones. Not everything in the old theatres of machines made sense -- not even ideas that survived from one to the next. Take the clockwork mill: to grind grain, Agostino Ramelli proposed using a huge weight-driven clockwork mechanism. Unfortunately, a mere boy was supposed to rewind the weight after it'd driven the mill through a huge gear train.

The whole advantage of the water-driven mill was that it generated a hundred times as much power as a human being. Now one boy was supposed to replace that power. Still, the folly of the idea seems almost worth it when we look at his lovely complex woodcut!

Clockwork was a primal concept of that age, and we see it again in Bartolemeo Scappi's spring-driven spit for cooking meat. Here's one of the few period pictures of a sixteenth-century watch mechanism. It's being used on a heroic scale to turn three large spits at constant speed.

Much of this was blatant showing-off. Still, stirred in among the flamboyance of machines that might or might not work is a record of the machines that underlay renaissance civilization.

We see accurate representations of the new production of rag-based paper, of a horizontal-water-wheel-driven grain mill, of a cam-controlled copper engraver's press, of a medieval fire engine.

These were the forebears of the handbooks that guided me through a lifetime of engineering. My Marks' Handbook is dated 1951 -- the year I finished college. It has over twenty-two hundred pages of compact information that I still reach for now and then -- for its graphs, illustrations, charts, tables. One day, twenty-fifth-century historians will turn to their three surviving copies to learn just how our world was made, five hundred years before.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Keller, A.G., A Theatre of Machines. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1964.

Mechanical Engineers' Handbook, (Lionel S. Marks, ed.) 5th Ed., New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1951

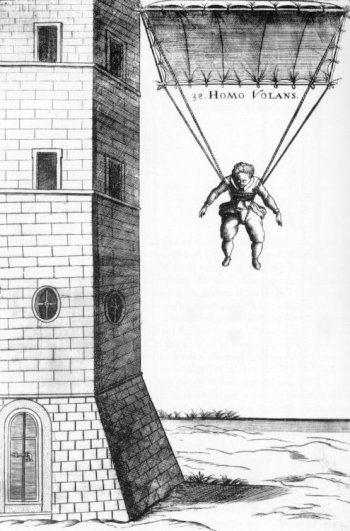

Verantius' suggested parachute design