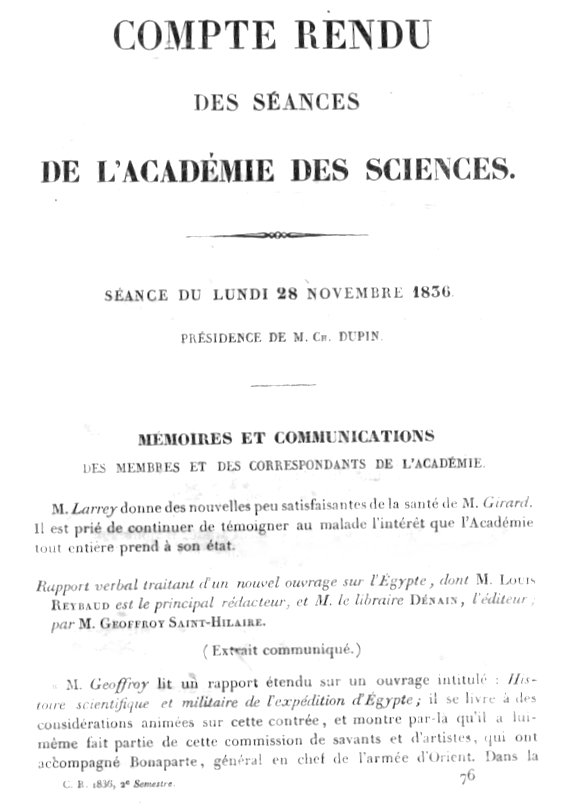

Comptes Rendus, 1836

Today, we read modern science when it was first being made. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Amazing what turns up in library stacks. Here's an 1836 edition of the French journal Comptes Rendus. It's the proceedings of the French Academy, and it's from a time when French analytical science was the strongest in the world.

To see what this remarkable volume really means, let's turn some pages: There's a lot of material from François Arago, then Perpetual Secretary of the Academy. Much of that is material he was passing on from all over the world. For example, he transmits a letter from Mary Fairfax Somerville in England. She reports on experiments with the spectrum of light. (Two years later, Arago would make basic contributions to that same field.)

The current president of the Academy was Charles Dupin. Dupin, like Arago, was a major voice in bringing the Academy back to a better appreciation of applied science. Both he and Arago had a keen appreciation for English industrial accomplishment, even if science belonged to France for the moment.

We find many of the mathematicians you may've studied in college: Cauchy, Liouville, Jacobi. Liouville has a short paper on how to solve a strange differential equation -- first derivative with respect to time equal to the third derivative with respect to position. I wonder where that might occur in nature! But I hold my tongue. For it was Liouville who set up means for dealing with many of the essential equations in engineering.

The chemist Gay-Lussac is there. So is von Humboldt of the Humboldt current, and Peltier, who explained how thermocouples work. Justis von Liebig (who set up the first modern R&D lab twelve years before) has two articles on chemistry. The English astronomer John Herschel reports on Halley's Comet. We find Navier and Poisson, who wrote the basic equation for viscous fluid flow.

I realize that you listeners can't possibly recognize all these names. But, coming from your scattered walks of life, you'll all recognize some. I've never, in my whole life, seen such a concentration of greatness in one volume of any journal.

I can think of two reasons why this is so: For one thing, we'd given up on pure rationalism and were, once more, stirring subjective creativity back into our science. For the next two generations, we would make remarkable strides. What began with these French analysts would finally give us Einstein.

But the other reason for all this greatness is one we should take to heart. It is that all science rests under one cover -- math, chemistry, biology, physics, astronomy, geology, geography. The French academy still presumed that we could read outside our field. Science lived in a room with no doors, and scientists all fed upon one another's ideas. This startling book reveals the pay-off of cross-fertilization going on at a level far beyond anything we dare practice today.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Comptes Rendus des Séances de L'Académie des Sciences. Paris: Bachelier, Imprimeur-Libraire, 1836.