John P. Parker

Today, we follow a slave out of slavery. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

John P. Parker was born in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1827. His mother was a slave, and his father was white. Most of what we know of Parker comes down through the transcription of an oral history from the late 1880s. That narrative takes up when Parker was sold away from his mother at the age of eight.

As he marched in chains from Norfolk to Mobile, a terrible knot of anger welled up in him. He tells of smashing blossoms along the trail with a stick -- of hating the flowers for being free.

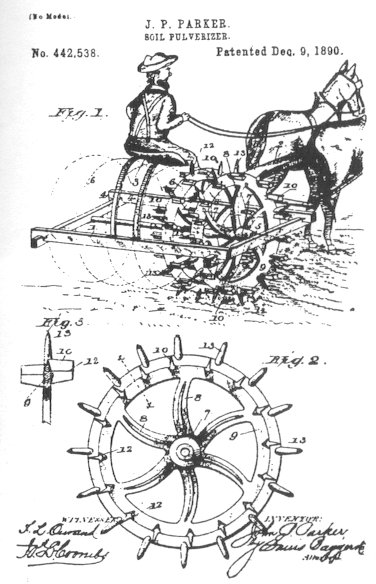

For eighteen years he tried to escape slavery. Meanwhile, he learned the trade of iron molding. At length he managed to save enough money to buy his freedom. He made his way north, married, and settled in the town of Ripley, Ohio, across from Kentucky. At first he worked as an iron founder. After the Civil War he went into business for himself. He created a foundry and a machine shop. He obtained patents for agricultural equipment. He became wealthy.

The writer who took down Parker's oral history wasn't interested in Parker's inventive and business successes. That part of the story barely appears in the biography.

The interview was driven, instead, by the popularity of the book Uncle Tom's Cabin. Harriet Beecher Stowe had fueled abolition sentiments and Civil War itself when she wrote about Eliza bundling up her baby and fleeing over melting ice to Ohio. Stowe later said that Ripley was the town to which a real-life Eliza had run.

A Congregationalist minister named John Rankin had been the center of intense Underground Railway activity in Ripley. He was credited with saving the real-life Eliza. But it was also Rankin who'd given Parker's rage at slavery the focus it needed. Working closely with Rankin, Parker had, for fifteen years, lived a double life. He'd founded iron by day. By night, he'd smuggled hundreds of slaves out of Kentucky and sent them on their way to Canada.

So the reason for going after Parker was only to verify the Eliza story. As it turned out, Parker had a much larger story to tell. Yes, he knew of Eliza, although he hadn't witnessed her escape. But the escape from slavery gains a reality we miss in Uncle Tom's Cabin when Parker describes his own commando raids into Kentucky. He tells of hairbreadth escapes, of being shot at, beaten, and for years carrying a thousand-dollar price on his head.

So Parker was tempered by risk, action, principle, and righteous anger. Out of that he wrested more than prosperity. He found intellectual fulfillment as well, and he sent his sons and daughters on to be educated at schools like Oberlin and Mount Holyoke.

Without the public's fascination over Eliza on the ice, Parker would've been just one more anonymous hero, one more lost story of triumph over hardship -- there were so many. It took the courage and tenacity of hundreds of John Parkers finally to free us all from the nightmare years we spent trafficking in human slavery.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Parker, J. P., His Promised Land. (Stuart Seely Sprague, ed.) New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1996. (This is a recently edited version of the oral history originally taken down by Frank M. Gregg in the 1880s and published in 1908.)

I am grateful to Richard Blackett, UH History Department, for suggesting Parker's story to me.

Drawings from one of Parker's many patents