A Tripartite Bridge

Today, a strange bridge. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

By design or by chance, you've all seen the Steelers playing in Pittsburgh's Three Rivers Stadium. It's called that because it lies just north of the point where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio. The rivers form a letter Y centered on Pittsburgh. The stadium is just north of the juncture.

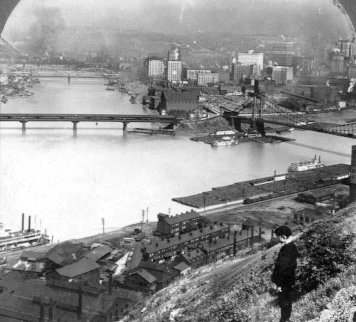

Today, bridges and tunnels criss-cross the three rivers. But when Pittsburgh was mushrooming into one of our major industrial cities, two centuries ago, bridges were a crying concern.

The young Prussian engineer John Roebling came to America in 1831 and tried to form a Utopian community north of Pittsburgh. Ten years later he gave up farming and went to work developing wound-steel cables for pulling barges. Then he realized he could revolutionize bridges if he used his cables to suspend them. Roebling began in Pittsburgh: an aqueduct suspended across the Allegheny, a 1500-foot bridge over the Monongahela. He went on to become America's greatest bridge builder. He bridged Niagara Falls. He eventually gave us his masterpiece, the Brooklyn Bridge. But the wildest Roebling bridge never got built. Joel Tarr and Stephen Fenves tell about Roebling's Tripartite Bridge.

The young Prussian engineer John Roebling came to America in 1831 and tried to form a Utopian community north of Pittsburgh. Ten years later he gave up farming and went to work developing wound-steel cables for pulling barges. Then he realized he could revolutionize bridges if he used his cables to suspend them. Roebling began in Pittsburgh: an aqueduct suspended across the Allegheny, a 1500-foot bridge over the Monongahela. He went on to become America's greatest bridge builder. He bridged Niagara Falls. He eventually gave us his masterpiece, the Brooklyn Bridge. But the wildest Roebling bridge never got built. Joel Tarr and Stephen Fenves tell about Roebling's Tripartite Bridge.

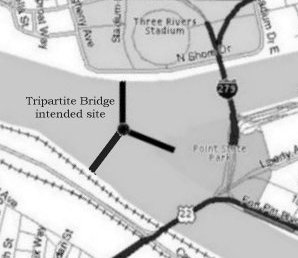

The Tripartite Bridge was to lie right where the three rivers meet. It was laid out like the center of a Peace Symbol — three branches radiating from a central point to link the three parts of the city. Each branch was a single span about a quarter-mile long.

The Pennsylvania governor okayed it in 1846, and stock went on sale. But competing forces rose up against the bridge. It would put ferryboat operators out of business. It would deflate real estate values in the city center. People were told it would block river traffic and take cash away from other important projects. In the end, no stock was sold, and the project was put on ice.

If the bridge offered any real problem, it was in the design. Suspension-bridge cables carry huge loads. They're usually anchored solidly into the earth. But here one end of each leg had to anchor at a central pier out in the water. Cable forces from three directions would have to balance one another at that pier.

Could Roebling have done it? Maybe he could've, but he died before the project was resurrected in 1871. This time, developers turned to Roebling's son Washington, who was finishing the Brooklyn Bridge. This time they gave up on John Roebling's cable-balancing act. This time one of the links would be a solid truss bridge that could anchor cables from the other two suspension branches.

But people still wouldn't invest. The project died a second time, and we're left with all the what ifs. Look at the tip of Manhattan, so much like Pittsburgh with a river on either side. Instead of the Brooklyn Bridge we could be looking at a three-way bridge connecting Manhattan, Brooklyn, and New Jersey. Technology is filled with what ifs and almosts like that. Maybe we should spend more time with the wonderful not quites of invention.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Tarr, J. A., and Fenves, S. J., The Greatest Bridge Never Built? American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Fall, 1989, pp. 24-29.

For more on the Roeblings, see Episode 1488.

The approximate layout of the Roebling's Tripartite Bridge

View of the Allegheny/Monongahela confluence early in this century

(old stereopticon photo)