Saving the Lore

Today, we have to save more than the endangered plants. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

An essay by Paul Alan Cox in a recent issue of Science magazine raises a point about endangered species that I hadn't really thought about before. I'd like to try this one out on you.

Cox is director of the National Tropical Botanical Garden in Hawaii. He tells of visiting Epanesa Mauigoa, an elderly Samoan woman. He tells of sitting with her, typing on his laptop while she talked about herbal medicines. The conversation stretched out over weeks. In the end she gave him 121 herbal remedies. One was for a disease she called fiva samasama (Samoan for hepatitis)! She used an extract from the wood of the homalanthus stem.

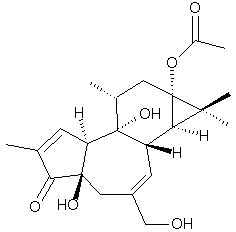

When the US National Cancer Institute learned of that one, they sent a team in to study it. The homalanthus stem has yielded a new antiviral drug, prostratin, and it's being studied as a possible cure for AIDS. If it succeeds, half the royalties are promised to the people of Samoa.

Much has been said about vanishing species of healing herbs. Cox himself notes that half the plant species in the Hawaiian Islands are on the edge of extinction. But Cox is concerned about more than just the extinction of plants. Without Epanesa Mauigoa, we wouldn't have prostratin, even if homalanthus survived.

Suppose the people of our world were suddenly replaced with people from the fourteenth century. How would they react? They'd wander among our machines not knowing what they did or what they were for. All our high technology would rust away while they moved into the countryside to recreate their old agrarian world.

That actually happened before in human history. As nomadic tribes moved into what'd once been the Roman Empire, they ignored the great buildings, roads, and support systems. They went about life as they knew it while vines grew over the great works of Rome.

Cox is really likening us to those seventh-century nomadic tribes. We jet about the world bringing our new technical culture into its far corners. The next generation of Samoans will no longer carry the knowledge of 73-year-old Epanesa Mauigoa. What she and others like her know is being lost even more rapidly than the plants from which she once made her medicines.

The terrible irony is that it would be monstrously self-serving to deny any people entry into the modern high-technology world we enjoy. We cannot isolate and freeze other cultures just to preserve their knowledge for our use.

The 1992 Convention of Biological Diversity established protocols for protecting and sharing these resources. They set goals for respecting, encouraging, and sharing traditional culture and knowledge. But I have a gnawing concern that it's too little, too late. I suspect that our grandchildren will walk among the old plants much as barbarians walked past the old ruins -- no longer able to see what they had once meant.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Cox, P. A., Will Tribal Knowledge Survive the Millennium? Science, Vol. 287, No. 5450, January 7, 2000, pp. 44-45.

Prostratin molecule, C22H3006 (left) | Homalanthus (or mamala) plant (right)