Thomas Sopwith

Today, we meet the oldest airplane designer. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

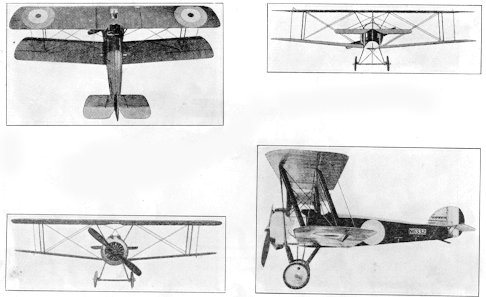

The airplane that finally brought down the Red Baron, Manfred von Richtofen, was an English biplane called the Sopwith Camel. It was a maneuverable little plane. My father, who flew them in France, told me they were tricky to fly. But with a good pilot, they were deadly in combat. In 1917, the Germans owned the air over the Western front. Then, that summer, the Sopwith Camels arrived. And control of the air shifted back to the allies.

It was called the Camel because the contour of its fuselage included a humplike cowl over the guns, in front of the pilot. And Sopwith referred to its maker, Thomas Octave Murdoch Sopwith.

The WW-I air war was, in large measure a duel between Sopwith and the maker of German airplanes, Fokker. Sopwith learned to fly in 1910, when he was twenty-two. By then, he'd raced automobiles and speedboats, and he'd done daredevil ballooning. In no time, he won flying prizes and used the prize money to start making airplanes. Like Fokker, he was a young airplane maker, ready for World War I.

During the war, he built 18,000 airplanes for the British. His early Sopwith Pup and Sopwith Triplane, along with the French Nieuports, dominated the air until 1916 when the Fokker Triplane appeared. But then the Camel reclaimed Allied air superiority.

Both Sopwith and Fokker were still under thirty in the fateful summer of 1917. Fokker came out with the superior Fokker D-VII in 1918, and he momentarily gave the game back to Germany. But then the French Spad and England's Sopwith Snipe restored Allied dominance. The Snipe became the mainstay of British air power for a decade after the war. The young Thomas Sopwith had done a remarkable job by any measure.

He stayed with airplane building after the war. In 1935 he was made Chairman of the Hawker-Siddley group, and there he did a remarkable thing. In 1936 he decided to produce a thousand Hawker Hurricanes on his own, without a government contract. War was brewing again, and if the government wasn't ready, Sopwith was. Without the Hurricane, England would've been laid bare against Nazi bombers in the early days of the Battle of Britain.

But even that was far from the last of Sopwith. After World War II, his company developed the Hawker Harrier -- the first jet airplane that could take off and land vertically. The Harrier was prominent during the Falklands War.

Sopwith celebrated his hundredth birthday on January 18th, 1988. The RAF sent flights of Sopwith's airplanes past his home near London. What a history lesson that was! An array of airplanes from early flying machines to modern jets -- a parade that called up the whole history of powered flight in the life of one man. For Sopwith had a perfectly uncanny ability to read the future. He died, by the way, a year later at the age of 101.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The British Dictionary of National Biography includes a short, but detailed and complete, biography of Thomas Octave Murdoch Sopwith. (The Internet also includes a great deal of material on Sopwith and his airplanes.)

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 84.

From: Notes on Identification of Aeroplanes, US Signal Corps,

Nov. 1917 (issued in France to 1st Lt. John H. Lienhard III)