Fokker's Interrupter Mechanism

Today, we meet a nice young man and his killing machines. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The first airplanes that took to the sky in WW-I had only one purpose -- scouting enemy positions and movements. Still, in no time at all, their pilots looked for ways to shoot each other down. Flyers made the first kills by firing pistols and rifles off to the side. Then backseat observers began operating movable machine guns. But what they clearly needed were forward-firing guns that could bring an enemy down from behind.

The British were first to mount forward-firing guns on the upper wing -- shooting over the propeller. But that made aiming hard, and it put the guns out of the pilot's easy reach when they jammed. The French took the next step. They put metal deflectors on the propeller so the pilot could fire straight through the blades, with a bullet glancing off now and then. That worked until crankshafts deformed under the hammering of their own pilots' bullets.

Enter now Holland's Anthony Fokker. The year before WW-I began, Fokker was only 23 and building airplanes. Germany contracted with him to build ten airplanes, and he went to work. War broke out months later, and Fokker was suddenly Germany's man-of-the-hour. By 1915 his monoplane, the Eindecker, was doing frontline scout work. Then the Germans brought him a captured French plane with metal plates on the propeller. Could he do that with the Eindecker? Fokker tells what happened next, in his autobiography:

They handed him the plane late on a Tuesday afternoon. Fokker said, "Wait a minute!" The way around the problem is to let the propeller fire the gun. The propeller turns at 1200 rpm, and the gun fires 600 times a minute. Put a cam on the shaft and let it fire the gun every other turn. Then no bullet will ever hit the prop. Fokker came back with a synchronized machine gun that Friday.

The device worked well enough in tests, but German officers wanted a combat demonstration. They wrapped the Dutch civilian Fokker in a German uniform and hustled him off to the front.

He took off in his Eindecker and soon spotted a two-seater French scout below him. He put the plane into an attack dive, located the scout in his sights, then realized he was about to kill two people! Fokker turned sick to his stomach and flew back to the aerodrome without firing a shot.

Let the Germans do their own killing, he vowed. So the Army relented. They sent a pilot named Ostwald Boelke up to try it out. Boelke went on to become Germany's first ace. Fokker went back to making the advanced German airplanes that killed thousands of Allied pilots throughout the war. The Allies called his mechanism The Fokker Scourge. After the war, we used Fokker's commercial airplanes here in America. My father, a newspaper writer, had been a pilot in France during WW-I. He met Fokker here. Later he told me what a thoroughly pleasant fellow he'd found Fokker to be.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Fokker, A. H. G., and Gould, B., Flying Dutchman: The Life of Anthony Fokker. New York: Arno Press, 1972, c 1931.

This is a substantially revised version of Episode 7.

1915 photo of Fokker's first synchronous machine

gun mounted on a Fokker Eindecker monoplane.

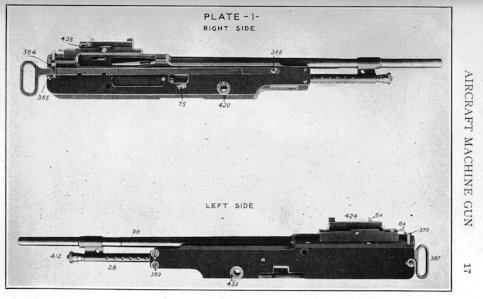

A page from the 1917 Marlin Machine Gun Manual.

By now the Allies also had interrupter machine guns.