Evariste Galois

Today, let's tell the remarkable tale of Evariste Galois. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Evariste Galois was the father of modern algebra. He was born in France in 1811, and died of gunshot wounds twenty years and seven months later. He was still a minor when his brief, turbulent life ended.

Galois began his career in math by failing the École Polytechnique's entry exam twice because his answers were so odd. He was accepted into the École Normale, only to be expelled when he attacked the director in a letter to the papers. A few months later, he was arrested for making a threatening speech against the king.

He was acquitted, but then he was right back into jail after he illegally wore a uniform and carried weapons. He spent the next nine months writing mathematics. Then, as soon as he got out, he was devastated by an unhappy love affair. I guess it'd be fair to say he was typical bright young teenager. Still, his talents as a mathematician were known. He did publish some material, and luminaries like Gauss, Jacobi, Fourier, and Cauchy all knew of him.

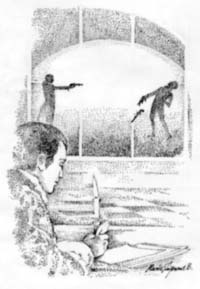

For some murky reason - most likely underhanded police work - he was challenged to a duel on May 30th, 1832. It was a duel he couldn't win but which he couldn't dodge, either. On May 29th, he wrote and wrote. That day and night he gathered the hundred or so pages of mathematics he'd produced during his short life. He wrote a long cover letter organizing explaining and expanding upon the work. Then and there, he set down what proved to be the very foundations of modern algebra and group theory. Some of the theorems in that package weren't proved for a century. He faced death with a cool desperation, reaching down inside himself and getting at truths we do not know how he found.

His fright and arrogance were mixed. The letter was peppered with asides. He wrote: "I do not say to anyone that I owe to his counsel or ... encouragement [what] is good in this work." But he also, desperately, penned in the margins, "I have no time!"

When poet Carol Drake heard his story, she wrote about it in two voices. The first voice is Galois's. He says, Until the sun I have no time. And the second voice replies,

But the flash of thought is like the sun --

sudden, absolute:

Watch at the desk, through the window raised on the flawless dark,

the hand that trembles in the light,

Lucid, sudden.

Until the sun

I have no time, ...

I cry to you I have no time -

Watch. This light is like the sun

Illumining grass, seacoast, this death --

I have no time. Be thou my time.

Well, the next morning Galois was shot. Two days later he was dead. But he'd done more for his world in one night than most of us will do in a lifetime because he knew he could find something in that singular moment when he really had to look inside himself.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Taton, R., Galois, Evariste. Dictionary of Scientific Biography (C. C. Gillespie, ed.). New York: Charles. Scribner and Sons, 1974.

This is a greatly revised version of old Episode 73.

Lines from the unpublished work: Antiphon for Evariste Galois (1957) are used with the permission of Carol Christopher Drake. The full text of the poem is:

Until the sun

I have no time.

But the flash of thought is like the sun --

sudden, absolute:

Watch at the desk, through the window raised on the flawless dark,

the hand that trembles in the light,

Lucid, sudden.

Until the sun

I have no time.

The image is swift,

Without recall, but the mind holds

To the form of thought, its shape of sense

Coherent to an unknown time --

I have no time and wholly my risk

Is out of time; I have no time,

I cry to you I have no time -

Watch. This light is like the sun

Illumining grass, seacoast, this death --

I have no time. Be thou my time.