Rain, Steam, and Speed

Today, a painting tells the coming of rail. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

It's a classic nightmare scene from movies of the '30s and '40s. You're in bed in a house near the train tracks. You hear a locomotive -- too loud, too close. Only at the last second, too late, the engine bursts through the wall and you realize your house isn't just by the track but on it. You are a dead man.

Steam rail systems were born in 1808 when Richard Trevithik ran a small demonstration line in London. Commercial rail service didn't begin until the late 1820s. In 1844, with steam locomotives still very new, the English artist Turner did a bizarre futurist painting of a train passing over a bridge. You've probably seen it. He called it Rain, Steam, and Speed: The Great Western Railway.

In the center is a train -- dark and shrouded by rain. Off to either side, a golden landscape, pastoral and rustic. Art historians have spilled a sea of ink upon that extraordinary picture. It is impressionist before the impressionists. It's a joyous celebration of our new technological power. It's as threatening as that locomotive about to burst through your bedroom wall in the dead of night. It shows the artistic world, and the technological world, together being turned upon their ear in the blink of an eye.

Other great artists joined Turner in seeing these moving engines as agents of upheaval. In 1855, American artist George Innes did an epic canvas of a primitive locomotive spewing smoke across the pastoral Lakawanna Valley. Tree stumps and distant smokestacks signal a world uprooted. By 1880, Monet, Pissaro, Manet, and Degas had all shown us their impressions of a way of life transformed by locomotives. In their work, the train station emerges as a new center of modern life. The menace fades.

But a stunning work done by the English painter Bury in 1831 shows a truly embryonic train slicing across the patchwork fields of England on a long, straight, willful line of track. Clouds gather over it. Turner's rain was just gathering.

Of all these paintings, Rain, Steam, and Speed is the most disturbing. Turner's indistinct and mystic train is crossing a very real bridge. He placed it upon the Maidenhead bridge built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel -- probably a conscious reference to the irrevocable change it brought with it.

When I was a boy, steam locomotives passed through the gulch, a block behind my house. We'd go to the tracks and stand as near as we dared when trains came by. The terrifying blast of the machine buoyed the heart of a ten-year-old. The danger was palpable. These last steam locomotives, a century after Turner, had lost none of their soul-lifting menace.

The artists of the mid-19th century saw it. They knew what those incredible engines were doing to their world. Turner's engine roars out of the mists of a twilight zone. It leaves the 18th century behind and hurtles straight into the world of my childhood.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

So much has been written about Turner's painting that I could fill pages and only scratch the surface of commentary. However, the initial trigger for this episode was: Carter, I., Rain, Steam, and What? Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 20, no. 2, 1997, pp. 3-22.

The history of railways has also been written in many places. Start with your Encyclopaedia Britannica.

For a remarkable image of the railway as a metaphor for power and change, see Link, O. W., and Hensley, T., Steel, Steam, and Stars, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987. (Even the title appears to play off Turner's painting.) See also Episode 556, and especially the quote from Whitman's Leaves of Grass included in it.

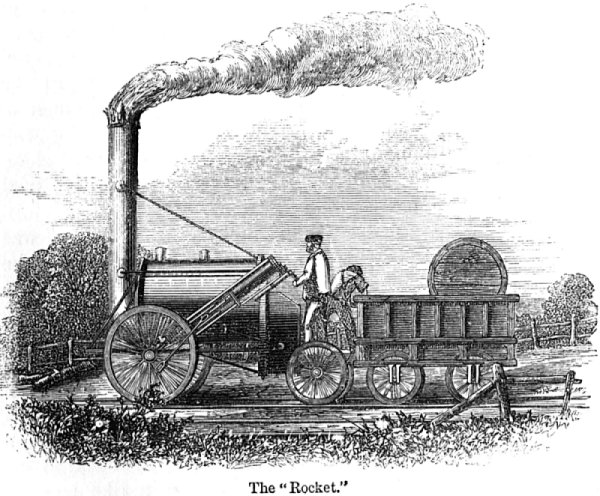

George Stephenson's Rocket locomotive (which might well be considered the

first fully evolved locomotive) from 1829, 15 years before Turner's painting.

From Samuel Smiles biography of George Stephenson